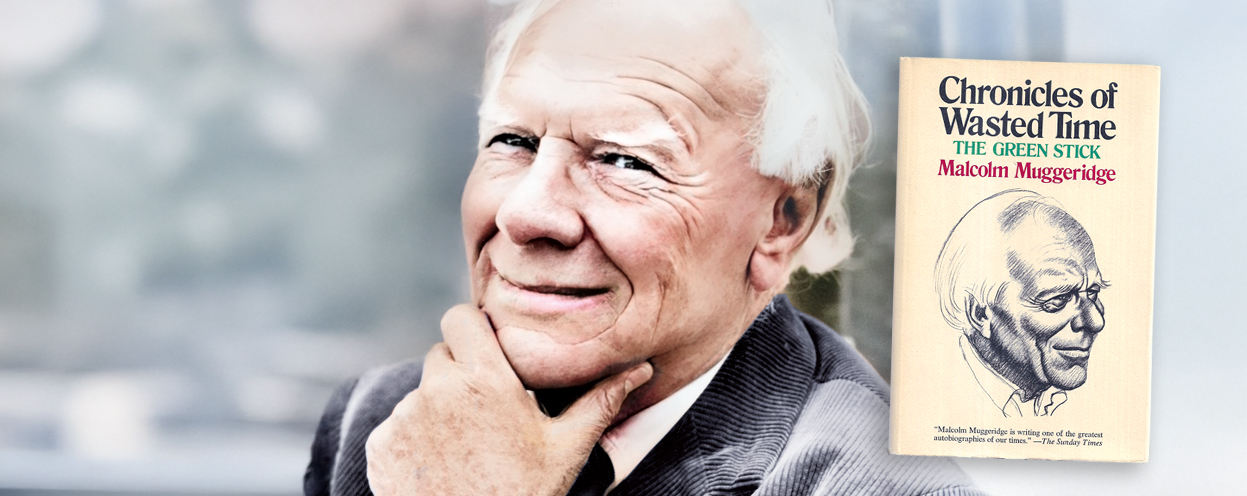

The Conversion of Malcolm Muggeridge

Malcolm Muggeridge’s reception into the Catholic Church in 1982 made loud headlines in the mass media. He was one of Britain’s most famous journalists, a best-selling author, consummate satirist, and producer of some of the best television programs of the twentieth century.

Malcolm Muggeridge was both a star of the “small screen” and a brilliant wordsmith whom many compared to G.K. Chesterton and C.S. Lewis. His conversion was not a sudden event like that of Saint Paul. As he stated himself, until the moment he joined the Catholic Church, he had had to “fight against something he knew would ultimately captivate and capture him.”

Childhood

Malcolm Muggeridge was born in London on March 24, 1903. His father was an agnostic, co-founder of the Fabian Society, and a member of the Independent Labor Party. At home the religion of socialist progress replaced that of Christianity. God was unnecessary as far as the Muggeridges were concerned. From his father, Malcolm took the conviction that man was capable of building a socialist paradise on earth—a just, peaceful, and prosperous society.

As a boy, Malcolm, unbeknown to his parents, acquired a copy of the Bible and read it “surreptitiously, as it might have been some forbidden book.” Guilt-ridden and shame-faced, he would read the Gospels, while making sure that nobody knew what he was reading. His reading of the biblical texts brought a mysterious new world to his ken. He even took the Scriptures to bed with him. He would pause over the fragments of text that touched him especially, most of these dealing with the passion and death of Christ. Another book that made a great impression on him at this time was Alighieri Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Cambridge

Malcolm began undergraduate studies at Selwyn College in Cambridge. There he befriended an influential seminary student by the name of Alec Vidler. The two men would become life-long friends. Thanks to their friendship, Malcolm was able to spend two terms in residence at the Anglican Oratory of the Good Shepherd, where he experienced the richness of religious community life. His daily activities included reading the holy office, attending Divine service, serious intellectual study, and manual labor in the gardens. Malcolm desperately sought help in matters of the Faith. He wanted to know what faith was and how he should acquire it. He prayed fervently for a visible sign of eternal life, but received no such sign. He had yet to learn that faith was an arduous journey engaging the soul in a fierce struggle with evil, which enslaved man and dulled his perception of the spiritual world. The brief religious experience would later enable Malcolm to understand that, “the ways of abstinence lead to happiness, while self-indulgence, especially in the area of sexuality, lead to unhappiness and remorse. To put aside worldly ambition, lechery, the ego’s clamorous demands, what joy! To succumb, what misery!”

Loss of faith

Toward the end of his studies, Muggeridge lost his faith and abandoned Christianity. Science became his substitute for religion. Upon graduating, he accepted a teaching post in India. The same insistent questions about the meaning of life followed him there. His discovery of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam did not diminish his enduring appreciation of the greatness and depth of the Christian faith. In a letter to his father in 1926, he wrote, “Christianity is to life what Shakespeare is to literature; it envisages the whole.” It was then that he became captivated by Chesterton’s book on St. Francis of Assisi and other works on the principles of faith (Orthodoxy, among others). He claimed that he loved Christ, but could not stand the institutionalized Church, since it “killed the living beauty of God.” In reality, however, he was placing all his trust not in Christ, but in the ideas of socialism.

On returning to England in 1927, Muggeridge taught school briefly in Birmingham. He was then convinced that man achieved inner harmony and happiness in a socialist state. “I am a socialist—he wrote—because I believe that the right conditions help man to be good, and only collectivism creates such conditions.” Shortly afterwards, Muggeridge received a teaching post in Cairo. He left for Egypt—this time with his wife. In Cairo he began his career in journalism as a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian.

In love with abstemiousness

Malcolm Muggeridge married Kitty Dobbs in a civil ceremony in the summer of 1927. His wife came from a wealthy family; like him, she was imbued with socialist ideas. Both considered themselves free from religious constraints, and so their marriage amounted to a contractual partnership that could be broken at any time. Their views on sex were ultra-liberal. Only after many years did they discover that their selfish pursuit of sexual pleasure, which led to numerous marital infidelities, was the cause of immense suffering both for their children and themselves. Whenever Muggeridge was unfaithful to his wife, he felt guilt-ridden. He felt contempt for his unbridled desires and longed for a pure heart. Later he would compare the pursuit of selfish pleasure to chasing after “a young hind, fleet and beautiful. Hunt her, and she becomes a poor frantic quarry; after the kill, a piece of stinking flesh.”

For the greater part of his life Muggeridge struggled with the lusts of the flesh. After each such spiritual struggle with chastity he would turn longingly to Christian principles, which held that true happiness could only be found “in the rejection of the ego, and not in succumbing to it, in turning away from fleshly lusts, and not in gratifying them.” Muggeridge did not silence the voice of his conscience. He did not try to justify his marital infidelities or call them good. He preserved a basic honesty and listened to his conscience. Such an attitude, after years of inner struggle, would lead him to faith and reconciliation with God and the discovery of the full truth in the Catholic Church.

Muggeridge wrote an essay on the sexual revolution, Down with Sex! Drawing on his observations and experience, he pointed to the depth of spiritual desolation and depravity caused by breaking the moral norms regulating the area of sexuality. He warned that the life-style promoted by the sexual revolution led to unspeakable unhappiness. On January 18, 1962, he wrote in his diary: “The one desire left to me in life is to extinguish in myself every form of selfishness, pride, lechery, cupidity. I want the dying flame of my existence to burn bright and unwavering and not to flicker out in a final splutter of smoke.” In an interview given in December of 1965, he acknowledged that he had succeeded in mastering his passions. “Man must make a decision: either to curb his lusts or succumb to them. I have conquered mine.”

Thence began the most beautiful period of Malcolm and Kitty’s life together: a period of great peace and happiness flowing from marital harmony. Both discovered the joys of chaste married life. They began to delight in each other as never before. Abstinence, self-restraint, asceticism, self-mastery in the area of the senses and feelings as a means of achieving spiritual freedom and the full enjoyment of life—all this flew in the face of the universally promoted life-style. Small wonder that Muggeridge’s attitude should have provoked waves of criticism and scorn on the part of the defenders and advocates of liberal sex who promoted hedonistic and permissive behavior.

Muggeridge’s attitude was not a relapse into Puritanism; rather it was the path to freedom and the full fruition of life. “Just now I am in love with abstemiousness,” he noted in his diary. “One should not give up things because they are pleasant (which is Puritanism) but because, by giving them up, other things are pleasanter.”

Transformation

Malcolm Muggeridge was uncompromising in his quest for the truth—both from a moral and intellectual point of view. Even as he fought against his selfishness and unbridled passions, he engaged in an intellectual struggle in the pursuit of truth. Totally imbued with the ideas of socialism in the early thirties, he embraced communism. Upon arriving in Moscow in 1932 as a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian, he was convinced he had come to a land where for the first time in human history there was no exploitation, a country in which equality, justice, and happiness flourished.

He was very soon disabused of this fiction. He had placed his belief in a utopia. He discovered that everything in the USSR was built on violence and lies. “In the beginning—he would write acerbically—was the Lie and the Lie was made news and dwelt among us, graceless and false.” Muggeridge came to the personal knowledge that communist ideology, when put into practice in the form of “real socialism,” revealed her true barbaric face: an appalling horror of totalitarian enslavement and genocide. He witnessed the Great Famine in Ukraine, which killed tens of millions of people. The famine had been coldly planned and brutally executed by Stalin to punish the Ukrainian peasantry for their resistance to enforced collectivization.

Meanwhile, the European elites continued to rhapsodize over the Soviet Union. A great many journalists, writers, and intellectuals, succumbing to political correctness and sheer opportunism, chose to deny the facts and wrote idyllic falsehoods about the situation in the communist “paradise.” Muggeridge described this phenomenon of blindness, stupidity, and intellectual dishonesty (he characterized these as “a peculiar sin of the twentieth century”) in his novella Winter in Moscow (1935), He was one of the few journalists who had the courage to tell the truth. He was the first to inform public opinion of the appalling crime of the Ukrainian famine. He dispatched his articles to the Manchester Guardian by concealing them in diplomatic pouches to prevent their seizure by communist agents.

Muggeridge’s sojourn in the USSR resulted in his utter rejection of the communist ideology, which had spawned totalitarian power, enslavement, and the crime of genocide. The experience prompted him to renew his interest in Christ and the spiritual life. In the great works of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, he discovered the mysticism of traditional Russian culture. For the first time in his life, while attending the Divine Liturgy in church with crowds of hungry, praying people, he experienced the joyous truth of Christ’s Resurrection. No power on this earth could overcome Him. Muggeridge felt a great longing to entrust his life, wholly and unconditionally, to Christ, who was all-powerful in His love and yet did not resort to means of coercion. He came to realize the catastrophic consequences of rejecting Christ and His teachings, for then man became unhinged and descended to levels lower than the beasts. Muggeridge felt a deep desire to become a Christian. He wrote: “For me the Christian religion is like a desperate love. I carry its image within me and gaze at it from time to time with wistful longing.”

The terrorism of liberal ideology

In 1944, disillusioned with the USSR and liberal ideology, Muggeridge began to consider entering the Catholic Church. He wrote in his diary, “I see the strength and importance of the Catholic Church, but I cannot in all honesty accept her dogmas.” Upon his return from Moscow, he realized the extent to which liberalism was destroying European civilization. Liberalism consummated itself in totalitarianism—it was in fact the precursor of totalitarianism. He observed that the insidious lie of liberalism lay in its denial of the fact that “left to his own devices, man becomes cruel, lustful, slothful, and prone to evil. The only way of curbing his evil proclivities is to awaken in him a fear of God or a fear of other people. Of these alternatives I place the former above the latter.” What ennobled man and inspired him to live a good life was the awareness of God’s justice and the fear that he could by his own choice forfeit eternal life.

Muggeridge defended Christianity even though he was not yet a Christian. He insisted that Christianity’s worst enemy was not Stalin or Hitler, but liberalism. He warned that for over a hundred years the civilization of death in the guise of liberalism had been undermining the foundations of Christian civilization, which defended the dignity of every human person, freedom of conscience, and the right to life from the moment of conception to that of natural death. The ideas of liberalism when put into practice stamped out the Christian ethic and every principle of conduct flowing from it, thus leading humanity to certain self-destruction.

In his autobiography Chronicles of Wasted Time, Muggeridge spoke of the destructive influence on European civilization of Freud and Marx’s views: “Freud and Marx undermined the whole basis of Western European civilization as no avowedly insurrectionary movement ever has or could. By promoting the notion of determinism, in the one case in morals, in the other in history, thereby relieving individual men and women of all responsibility for their personal and collective behavior.” Muggeridge stressed that not Charles Darwin, nor Karl Marx, nor yet Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, but rather Jesus Christ was the foundation of European civilization. Liberalism was a negation of everything revealed to man by Christ. When man rejected Christ, then the search for hope became hopelessness, the pursuit of happiness, ultimate despair, and the will to live—a death wish.

Muggeridge fought uncompromisingly against the “soft” terrorism of liberal ideology. In 1968, he resigned his position as rector of the University of Edinburgh. He resolutely opposed the demands of the students who called for the legalization of LSD on campus and the distribution of the contraceptive pill. In his resignation speech, he derided the students’ demands. He compared the moral state of the times to that of the Roman Empire in its period of decadence. “How infinitely sad, how macabre,” he said, “that the form of their rebellion should be a demand for drugs, for the most tenth-rate sort of self-indulgence ever known in history.” “Dope and bed!—he added—the resort of any old slobbering debauchee anywhere in the world at any time.”

The sacredness of life

Muggeridge was always convinced of the sacredness of human life. He understood that separating the creative impulse from procreation wreaked terrible devastation in the moral sphere: in attitudes, behaviors, and interpersonal relationships. It led “to the downgrading of motherhood and the upgrading of spinsterhood, [to] the acceptance of sterile perversions as the equivalent of fruitful lust, [and to] the grisly holocaust of millions of aborted babies.”

In 1978, Muggeridge predicted that in the not-too-distant future European countries would succumb to the temptation of legalizing euthanasia as a means of “liberating” the individual and freeing the electorate from the mounting burden of caring for the sick, the aged, and disabled. He perceptively predicted that while those who had lived through the Nuremberg Trials were still alive it would halt what would become an irresistible pressure to legalize euthanasia. “It takes just over thirty years,” he added, “in our humane society to transform a war crime into an act of compassion.” He underscored the painful fact that abortion and euthanasia represented a kind of “humanitarian holocaust,” which was killing many more human beings than in Hitler’s time.

Muggeridge took an active part in the defense of Pope Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae vitae. At the 1978 San Francisco conference devoted to the encyclical, Muggeridge stated in his address that sexuality had to be understood as a sacrament of love, the basis of the indissolubility of marriage and the family. He considered Humanae vitae as a document of supreme importance to all of humanity. History would bear out the rightness of the Church’s position on the question of contraception. To hold such a position was an act of great civic courage on Muggeridge’s part. He was after all opposing the dominant propaganda of the time, which saw the legalization of contraception and abortion as a sign of emancipation and the liberation of women.

Muggeridge fought against the contraceptive mindset, defending the sacredness of life from the moment of conception to that of natural death. The Church’s teaching of the sacredness of life, he maintained, provided the only effective antidote to the crimes of abortion and euthanasia (which he called the Liberal Death Wish). On hearing the term “unwanted child,” he would mention how Mother Teresa, when holding up a newborn child she had just rescued from a Calcutta trash-heap, would say with a smile, “See? There’s life in her.”

Almost home

Malcolm Muggeridge was relentless in his pursuit the truth. In this quest he found strong support in the writings of the great convert Saint Augustine of Hippo and that fourteenth-century masterpiece of Christian mysticism, The Cloud of Unknowing. But the deciding factor in his conversion was his meeting with Blessed Mother Teresa in the spring of 1969 when he was making a documentary film on the Missionary Sisters of Charity. He would write: “Mother Teresa is, in herself, a living conversion; it is impossible to be with her, to listen to her, to observe what she is doing and how she is doing it, without being in some degree converted. Her total devotion to Christ, her conviction that everyone must be treated, helped, and loved as if he were Christ himself; her simple life lived according to the Gospel and her joy in receiving the sacraments—none of this can be ignored. There is no book that I have read, no speech I have heard, or divine service I have attended; there is no human relationship or transcendental experience that has brought me closer to Christ or made me more aware of what the Incarnation means and what is demanded of us. What, then, is a conversion? The question is like asking, ‘What is falling in love?’ There is no standard procedure, no fixed time.”

The witness of Mother Teresa awoke in Muggeridge’s heart a love of the Catholic Church; yet it would take another thirteen years before he would finally decide to become a Catholic. His book Jesus Rediscovered, published in 1969, indicated his attempt to consider himself a Christian without affiliation to any particular church.

Muggeridge was now aware that pride, which separated man from God, and sensuality, which bound him to the earth, constituted the worst spiritual diseases. He began to feel remorse over his squandering of the better part of his life. He expressed his regret in the words, “You called me, and I did not come—all those idle years, idle words, idle passions.”

He made a strong resolution to live out more fruitfully the years remaining to him. He supported the mission of Mother Teresa and provided assistance to the mentally handicapped of the L’Arche Community founded by Jean Vanier. He considered Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, Simone Weil, and Jean Vanier to be the most important contemporary Christian writers.

In the mid-1970s, Muggeridge jettisoned his own TV set, telling everyone he had had his “aerials removed.” The television, he maintained, was the “repository of our fraudulence,” the camera, “the most sinister of all the inventions of our time.” “Man—he stated in an interview in 1981—has created in this century such a fantasy machine as has never before existed. Wherever you find yourself, these fantasies are present, suggesting to you that happiness is achieved through carnality, that fulfillment in life is found in worldly success.

Muggeridge warned against the dangers of flight into the unreal, virtual world created by the mass media and advertising industry: “Never before in the history of mankind have the banal material aspects of life been presented in such a glamorous light, prompting people to want more and more things, inculcating in them the conviction that joy and the greatest happiness obtain from carnal things.” Reality, he insisted, was something “we need to penetrate, embrace, and love as our greatest gift,” since present in this reality was the Incarnate God—Jesus Christ; and this was achieved through prayer.

Home at last

Muggeridge’s Catholic conversion was the crowning point of a long process of spiritual maturation. With great humility he accepted all the truths revealed to man by God and taught in its fullness only by the Catholic Church. He lamented the length of time it took him to reach this point.

Malcolm and his wife Kitty were received into the Catholic Church on November 27, 1982, in the chapel of Our Lady Help of Christians, Hurst Green, Sussex. Presiding over the ceremony was the Bishop of Arundel Diocese, Fr. Cormac Murphy O’Connor. As Muggeridge put it, his conversion came with “a sense of homecoming, of picking up the threads of a lost life, of responding to a bell that had long been ringing, of taking a place at a table that had long been vacant.”

Muggeridge discovered the joyous truth of the good and merciful God, who did His utmost to lead the greatest sinners to repentance. Man was free and could lose contact with God. He could immerse himself in sensuality and exalt himself in his pride. He could scorn his Creator. In his folly man could curse God, ridicule believers, and even proclaim that God was dead. But at the end of his earthly life there was only one thing left for him to do: to fall on his knees and entrust himself in humble prayer to the Divine Mercy. If he failed to do so, the terrifying eternity of hell awaited him. If he did so, he would experience the infinite mercy and loving-kindness of God and the indescribable joy of having all his sins forgiven.

Having with all his heart accepted the treasure of faith, Muggeridge proceeded to order the rest of his life to its demands. We read in the Letter to the Hebrews that, “faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen” (Heb 11:1). Muggeridge maintained that faith was a special kind of knowledge, since it involved accepting the fact of a veil of mystery separating time and eternity. Faith enabled us to enter into this mystery and make personal contact with Jesus Christ, who, being true God, became true man that He might free us from enslavement to Satan, sin and death.

After his conversion, Muggeridge fostered a special love of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. Holy Mass became the central event of his day. Increasingly, the spiritual life took on for the Muggeridges a greater reality than that of the sensual world. Together they lived out the rest of their days in silence, without a TV, detached from the world, devoted entirely to God in their long daily prayers. Retiring into mysticism, they prepared themselves for the supreme moment of their meeting with Christ at death.

In 1988, two years before his death, Muggeridge wrote: “I have always felt myself a stranger here on earth, aware that our home is elsewhere. Now, nearing the end of my pilgrimage, I have found a resting place in the Catholic Church from where I can see the Heavenly Gates built into Jerusalem’s Wall more clearly than from anywhere else, albeit if only through a glass darkly.”

In 1989 his health and memory began to deteriorate. God heard his prayer for total purification, “Humble my pride.” Having received the last rites, Malcolm Muggeridge departed this life on November 14, 1990. He passed through the Heavenly Gates. His life was proof that God “is found by those who do not put him to the test, and manifests himself to those who do not distrust him; because wisdom will not enter a deceitful soul, nor dwell in a body enslaved to sin” (Wis 1:2,4).

Sources:

M. Muggeridge, The Spiritual Journey of a Twentieth-Century Pilgrim, Harper Collins, 1988;

M. Muggeridge, Jesus Rediscovered, London, 1969;

Gregory Wolf, Malcolm Muggeridge: A Biography, London, 1995;

Joseph Pierce, Literary Converts, Ignatius Press, 2000.