Saint Joseph’s Saint: Brother André Bessette (1845-1937)

On October 17, 2010, there took place in the Vatican the solemn canonization of Brother André (Alfred Bessette), a Canadian religious, who initiated the building of Montreal’s St. Joseph’s Oratory, the world’s largest shrine to Saint Joseph, which draws millions of pilgrims.

This simple doorman, a lay brother of the Congregation of the Holy Cross (Congrégation de Sainte Croix) and in poor health throughout his life, had the gift of healing all those who consented not only to a physical but also a spiritual healing. Those who were not so agreeable experienced no healing. There thronged to him thousands of people whom he would simply entrust to Saint Joseph, encourage to wear a medal of the saint, and advise to anoint themselves with oil that had been used in the votive lamps before the statue of Saint Joseph.

Orphan and economic migrant

Alfred Bessette was born on August 9, 1845, in the village of Saint-Gregoire d’Iberville not far from Montreal, one of thirteen children of Isaac and Clothilde Bessette. When he was nine years old, his father, a woodcutter, was killed at work. Two years later, his mother died of tuberculosis. It was then that he began to suffer from a stomach neurosis, which brought on pains and vomiting after practically every meal. The condition would afflict him for the rest of his life. The eleven-year-old boy found himself in the charge of distant family members, who lived a life of grinding poverty. No one bothered about his health or education. He never went to school and barely learned to write his own name. The one food he could eat without suffering was a thin starch soup. For his First Holy Communion, which he made at the age of twelve, his Aunt Nadeau gave him a small crucifix. This article he would keep by him all his life.

On turning eighteen, he left home to seek gainful employment in the USA. Taking with him “a few rags and the crucifix,” as he would later recall, he set off to work as a railroad navvy. There, during the years of the American Civil War, he discovered a world of heavy labor and exploitation. He had to contend with his physical frailty and short stature (he stood barely four foot nine), and, above all, the heavy burden of his orphanhood and poverty. Turning to Saint Joseph for help, he asked him to become his foster father as well.

By way of the cross to the Congregation of the Holy Cross

In 1867, after four years of toil on the railroad, the twenty-two-year-old Alfred returned home, whence he had received news of the founding of an independent Canada as a federal state following the unification of the British colonies north of the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. As usual, his baggage consisted of little more than a few articles of clothing and the crucifix he had received from Aunt Nadeau. In his pocket he carried his earnings—a meager sum for someone returning from the US. The young man had no interest in finding a bride for himself. He preferred instead to sit in the silence of the churches, where he prayed to his adoptive foster father. He went to Farnham, where he hired himself out as a helper to Fr. Édouard Springer, a Protestant convert and vigorous builder of the Church. Gradually, there matured in Alfred a desire to enter the Congregation of the Holy Cross, which was based not far away at Saint-Césaire. He applied there on November 22, 1870. The novitiate house was in Côte-des-Neiges, which now lies within the boundaries of Montreal and where stood the Collège Notre-Dame, a well-known boys’ boarding school run by the Holy Cross Fathers. A month earlier, the master of the novitiate, Fr. Julien-Pierre Gastineau, had received a letter of reference from the parish, informing him that a “saint”” would be applying to the community. On December 8 of that same year, Pope Pius IX declared Saint Joseph patron saint of the Universal Church. Reading a great sign in the near conjunction of these dates, Brother André would never forget the event.

Problems arose almost from the first day. Being physically frail and practically illiterate, André (the religious name he adopted) was not suited for an apostolic congregation. His novitiate lasted three years, during which time he was forced to leave the community for a while. However, he was not discouraged, for, while living alone, he remembered he had the Family of Nazareth for spiritual companionship. From the Holy Family he learned more about the essence of community life than that great novitiate house could teach him; nevertheless, he suffered keenly on account of what seemed to him as yet another instance of orphanhood.

Finally, the new superior stated. “Even if this boy is not suited for work, he can at least pray well.” And so, on February 2, 1874, Brother André was allowed to profess his perpetual vows. They assigned him the duty of doorman, which he would carry out diligently for over thirty years. Joking about his job in the congregation, he would say, “They showed me the door, and there I stayed” (On m’a mis à la porte et j’y suis resté).

Hermit in the community

As doorman of the Collège Notre-Dame, Brother André led the life of a hermit. A bench by the entrance served him for a bed. There he ate his starch soup (the meals at the refectory did not agree with him), prayed, and read from the three books he always kept close at hand: On the Imitation of Christ, The Life of St. Gertrude, and The Four Gospels in One. He looked after the college pupils, buttoning up their coats and wrapping scarves about their necks, admitted the visiting parents, and took care of the occasional visiting beggar. Before long it was not just beggars knocking at Brother André’s door. Word began to spread that he prayed for the sick and gave out medals of Saint Joseph and oil, which had been used to light the lamps before the statue of the Guardian of the Holy Family. People would walk away feeling uplifted, and some, healed. They began prevailing on Brother André to visit the sick in their homes. This was not easy to arrange, as there was no one to take his place at the door; so he usually went at nighttime.

His superiors became alarmed on receiving reports that their brother doorman was practicing charlatanry, deserting his post, and, worse still, admitting contagiously sick people into the building, where schoolchildren were present. Physicians, jealous of their reputations, urged the superiors to forbid Brother André from carrying out his practices. Not a few felt mortified that a little religious without diplomas should be ribbing their paralyzed patients to stop malingering and to get to work, sending pupils with pneumonia out to the football field, and anointing festering wounds with votive lamp oil. However, the superiors showed more understanding than their counselors. “If it is of human origin,” they replied, “the thing will die out on its own and the fraud will come to light sooner or later. But if it is of divine origin, let us leave Brother André in peace; after all, he is doing no one any harm.” Privately, however, they asked him what he would do, if they forbade him from healing people. “I would stop doing it,” he replied without hesitation. That was good enough for his superiors. Still, to be on the safe side with the children, they suggested he should receive the sick at the nearby streetcar stop.

Dream of an oratory

Opposite the Collège Notre-Dame stood Mount-Royal—the mountain that gave its name to the city of Montreal, which was built around it. Looking at the mountain, Brother André dreamed of having a chapel built there in honor of Saint Joseph. Thanks to his persistence and the generosity of sponsors, who donated not only money, but also building materials and their own labor, Brother André’s dream became possible. Construction began in the winter of 1903. André received permission from his superiors and the city authorities to erect a small St. Joseph’s oratory on Mount-Royal. Trudging knee-deep through the snow, the doorman, his superior, and another brother finally reached the summit. The superior indicated the spot. “This should be good,” he said. “This is where we will put the chapel.” Brother André shook his head. “I’d prefer to see it there,” he said, pointing to a spot nearby. The superior found this odd disagreement over a few yards puzzling. “Because that’s where I saw it,” the little brother added in a soft voice. To this reservedly expressed but deeply felt “that’s where I saw it,” the superior yielded sway.

Construction began in earnest. By October 1904, the local press was talking about the first Saint Joseph’s Oratory, which, in addition to the celebrant, could barely seat ten people. People began to throng to Mount-Royal. Before long, benches were needed, as more and more pilgrims were coming to attend the Holy Mass celebrated by the congregation fathers. Brother André would sit under a birch tree and talk with the sick. He always responded to their requests for healing in the same way: “I will pray for you to St. Joseph. Allow your soul to be healed as well. Go first and make a confession, and then come back to me, if you like. Wear this medal, and take a little oil.” Responding to the rising interest in his own person, he would calmly explain: “It is not I who work the healings, but God; and it is Saint Joseph who pleads for them. So thank them.” He could talk about the Guardian of the Holy Family for hours, as if he lived with him every day under the same roof. To those who felt their prayers were not being answered, he would say, “Ask Saint Joseph that your prayer be such as he would raise to God in your place.”

Letters began to pour in. News of the wonder-working brother had spread not only throughout Canada, but also the United States. Scores, hundreds, thousands of letters: and yet Brother André could barely read or sign his name! So they assigned him a secretary. From 1909 on, they lived together by the chapel on Mount-Royal. The dream of the orphan, who had found a foster father in St. Joseph, began to be realized. A year later, a young priest from André’s congregation permanently joined the small community by the Oratory. The young priest’s name was Adolphe Clément, and he was blind. On arriving on the mountain, he sighed, saying how much he wished to pray the breviary and celebrate Holy Mass. Brother André slapped him on the shoulder, saying. “Go and have a good sleep. You will begin tomorrow.” The following morning Fr. Clément regained his sight. In 1909-1910 alone, 112 complete physical healings were recorded, as well as over 4300 instances of improved health, and countless more of spiritual graces received.

Phenomenal expansion and a farewell

But was it that little chapel seating ten people that Brother André “saw” in his dream? If that were the case, he would not have labored to gather additional funds for its expansion. In 1913, architects Alphonse Venne and Dalbé Viau drew up plans for a new basilica, which would stand on Mount-Royal. Five years later, the crypt, which could hold a thousand pilgrims, stood completed. It kept its original name: The Oratory of Saint Joseph. By late 1937, the basilica lacked only the projected dome, which was to be reminiscent of that of St. Peter’s Basilica, only slightly smaller and more austere. None other than John D. Rockefeller, in his declining years, would finance the dome.

Here at last the sick and the disabled could find solace. Past telling the number of those who went away healed! Brother André wrote no memoirs; kept no books. All the known accounts of healings come from witnesses. But the little brother was growing tired. He was over ninety years old. People were incredulous that anyone could live his whole life occupied daily with hundreds of people, and nourished only by water thickened by a little bit of flour, and suffering chronic infections and bleeding. Some asked in disbelief, “He can heal others; so why can’t he heal himself?”

Besides physical pain, Brother André suffered anxiety attacks throughout his lifetime. At night he had a child-like horror of the darkness. Upon him fell the spiritual consequences of setting others free from the Evil One. Nor did his way of the cross lack for sarcastic and slanderous attacks aimed at his person. His only defense was in entrusting everything to Saint Joseph and in loving and worshiping the Holy Trinity. At last, utterly exhausted, Brother André landed in hospital on December of 1936, where he died at dawn on January 6, 1937.

It was the Feast of the Three Kings, the day when, in the cave in Bethlehem, the astonished and silent Joseph received the guests who had come from far lands to pay homage to the Christ-child. On that day too, Saint Joseph received André that he might never again feel like an orphan.

Brother André’s funeral drew over a million people. For a whole week, they passed by his casket as he lay in state at the Oratory. There they could touch his feet, his hands, and kiss his wrinkled brow. Films recording the event remain preserved to this day. Canada bade farewell to a little man, through whom the whole country, from the highest authorities down, renewed her devotion to Saint Joseph. Battling a strong icy wind, the pallbearers carried the casket with the body of Brother André to the Cathedral for a solemn Mass of Christian burial. The body was interred in the Oratory crypt.

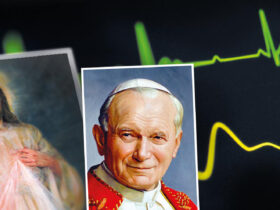

Brother André’s cause for canonization began in 1960. Three years later, a solemn exhumation revealed his body to be incorrupt. Pope John Paul II celebrated his beatification in Rome on May 23, 1982. Finally, on October 17, 2011, Pope Benedict VI canonized Canada’s first male saint. Thus Brother André became the Universal Church’s saint in honor of Saint Joseph. Like his adoptive foster father, André loved silence, humility, and the simple considerate gestures, which, at the Oratory, speak to countless throngs of pilgrims weary of the deluge of modern elixirs, which fail to bring healing.