The Treasure of Faith

Nobel Prize laureate Alexis Carrel decided to cast off the straitjacket of atheism when at Lourdes he witnessed the miraculous healing of his patient who was dying of peritoneal tuberculosis.

After his conversion, Alexis Carrel understood the truth of the texts of Holy Scripture: “For all men who were ignorant of God were foolish by nature” (Wis 13: 1); “Ever since the creation of the world [God’s] invisible nature, namely, his eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse” (Rom 1: 20). Who are “they”? Those “who by their wickedness suppress the truth” (Rom 1: 18).

Alexis Carrel was born in 1873 to a well-known, wealthy family in the small locality of Sainte-Foy near Lyons. His parents were owners of a textile factory. When Alexis was five years old, his father died, thus leaving his wife with the heavy burden of raising their three young children: Alexis (the eldest), Joseph, and Marguerite. Madame Carrel was a deeply devout believer. In this spirit she raised her children, teaching them the truths of the Catholic faith and morality. At the age of twelve, Alexis made his First Holy Communion. He attended a school run by the Jesuits where he showed signs of outstanding ability in the exact sciences.

The tragedy of loss of faith

After finishing his first year of postsecondary studies, Alexis decided to specialize in the field of surgery at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Lyons. There he gave further proof of his exceptional abilities. He had an extraordinarily creative imagination and an overpowering desire to perfect his knowledge and discover the mysteries of the human organism. Very quickly he became skilled in performing the most difficult operations. He constantly sought to perfect his surgical technique. With this aim in mind, he began taking lessons in needlework. Before long he had acquired such skill in this area that his sutures were almost invisible. He was the first to develop a method for stitching arteries.

In 1901, having completed specialist studies at the Universities of Dijon and Lyons, Carrel received the title of doctor of medicine and began to teach anatomy; in addition, he published articles, delivered public lectures, and carried out research. The new methods developed by the young Carrel did not meet with a favorable response from the academic milieu. Common envy and intellectual narrow-mindedness were the main reasons.

During his studies Carrel fell under the spell of rationalistic philosophy, which questioned the possibility of knowing God. Alexis came to see God as a construct of the human consciousness rather than as a real “self-contained being” and Creator—the sole source of all that exists. Carrel simply believed that God did not exist and that man could decide for himself what was good and what was evil. Anything that could not be proven by experience or reasoning was of no value to Carrel. He did not realize then that loss of belief in God was the greatest misfortune and tragedy in the life of man.

Alexis’ mother suffered greatly on account of her son’s atheism. She tried to convince him of God’s presence in the world by telling him of the apparitions of the Blessed Mother at Lourdes, and she prayed for his conversion. At the time, the Catholic press was devoting a great deal of space to the miraculous healings at Lourdes. Sincere in his quest for truth, Carrel did not dismiss these claims out of hand, but preferred rather to examine them at first hand and determine their reliability. On reading Emile Zola’s defamatory book on Lourdes, Carrel became entrenched in the conviction that the “miraculous” healings were the result of autosuggestion. But he encountered a dissenting view in the books of Dr. Gustave Boissarie, Director of the Lourdes Medical Bureau, who was responsible for documenting the scientifically unexplained healings occurring at the Shrine. Dr. Carrel acknowledged that there were healings described there that merited examination; nevertheless, he was convinced that science could explain them. All this only increased his desire to travel to Lourdes and examine the extraordinary incidents at first hand.

Journey to Lourdes

In May of 1903, Dr. Alexis Carrel was invited to accompany a group of invalids on a pilgrimage to Lourdes. The train with its 300 pilgrim-passengers departed from Lyons to Lourdes on May 26. Prior to their departure, Dr. Carrel carefully examined the sick (among them the 21-year-old Marie Bailly in the final stages of peritoneal tuberculosis) and scrupulously set down his observations. On the train Carrel had occasion to talk at length with a priest who for 25 years had been organizing annual pilgrimages to Lourdes. Each time, according to the latter, out of a group of around 300 invalids, some sixty had experienced the grace of healing. As for the rest, they returned home strengthened in their faith, filled with joy, and convinced that their suffering was a great grace when offered up to Christ. If the sick united themselves with the Suffering Christ—explained the priest—then they received the grace of cooperating in the suffering of Jesus for the salvation of the world, thus contributing to the conversion of sinners and atheists and saving them from eternal destruction. Carrel, who did not believe in God and even more so in the possibility of a miracle, found the priest’s testimony bizarre and untrustworthy. He wrote in his notebook: “If there occur in Lourdes supernatural phenomena of the kind related in the pious chronicles, what will be easier than to examine them without prejudice and partiality in the same way as we examine a patient in hospital or conduct an experiment in the laboratory.”

At the outset of the journey, Carrel was asked to administer a morphine injection to the 21-year-old invalid, Marie Bailly, who was in the terminal stages of peritoneal tuberculosis. Her parents and brother had died of the same disease. Marie could not sit up; she spat up blood, and vomited frequently. Her stomach was badly swollen. She suffered greatly and prayed a great deal. In particular, she prayed for the conversion of her cousin, a journalist, who was an atheist. Marie had a premonition that at Lourdes she would find a healing and that her cousin would be converted. Her doctors and family were against her making the journey. Eventually they relented, for they treated her request as her dying wish. Carrel administered the morphine injection to reduce her suffering. At 3:00 a.m., he had to give her another shot for her pain. He noted then that Marie had a high temperature, swollen legs, and a distended stomach; around her navel there was a large blister filled with water. These were typical symptoms of peritoneal inflammation attending tuberculosis. Carrel knew that Marie could die at any moment.

The train journey to Lourdes took about fourteen hours. On reaching their destination, the pilgrims expressed their great joy with prayers and loud singing. Carrel was amazed by the ardent faith of the pilgrims. Despite their great exhaustion, all were joyful and filled with the hope of a healing. Among the pilgrims there was a former schoolmate of Carrel’s who had volunteered to assist the sick. Alexis marveled at his simple, child-like faith. As to the rest of the believers, he watched them with pity. He was convinced they were living in a make-believe world. Yet in the depths of his heart, under the carapace of his atheism, there was a burning ache caused by uncertainty and the unfulfilled desire for a love stronger than death. Carrel’s schoolmate told him of miraculous healings he had seen at Lourdes with his own eyes.

Alexis explained that these healings were caused by the power of suggestion emanating from the hysteria of the pious multitude; that these were imaginary rather than organic healings. Then his friend told him about Pieter de Rudder who had fallen under a tree and suffered a crushing fracture to the two bones (tibia and fibula) of his left leg. For eight years de Rudder’s bones refused to knit together. The lower part of his leg hung like a limp rag. A suppurating wound concealed the point of fracture. On April 7, 1875, Pieter experienced an instantaneous and total healing after praying at the Flemish shrine consecrated to Our Lady of Lourdes. This spectacular miraculous knitting together of bones was documented by X-ray photographs. Carrel admitted the healing was mysterious, but in his opinion one ought to be skeptical even in such cases. “If God existed, miracles would be possible,” he stated, “but since God does not exist, then science will eventually explain even these kinds of incidents.”

Carrel was certain that miracles were an absurdity. He had come to Lourdes to be a good recording instrument, and if with his own eyes he were to see an instantaneous healing of an organic disease, the regeneration of an amputated leg, the disappearance of a cancer, a scarring wound, then, and only then, would he believe in miracles and the existence of God. And, pointing to Marie Bailly who was dying of peritoneal tuberculosis, he said: “If this girl is healed, that would be a real miracle. I would believe in it all, and become a monk.”

Miraculous healing

Before escorting the sick to the Grotto of Apparitions, Carrel went to Marie Bailly’s stretcher, to examine her. The girl’s condition was critical: she could not speak, she breathed with difficulty, her heart was growing weaker, he pulse was rapid and uneven, and her stomach was distended. A classic case of death agony resulting from peritoneal tuberculosis. Carrel was reluctant to allow them to take Marie to the Grotto. But the strenuous entreaties of her guardian convinced him that it would be cruel to deny the invalid her greatest wish. Together with two other doctors and his school friend, Carrel accompanied her to the Grotto, never leaving her side. They did not immerse Marie in the spring, but only sprinkled her with the water, then placed her before the Grotto. A brown blanket covered her emaciated body. Her bluish face was pale as a corpse, and her distended stomach bulked large under the blanket. Staring at the dying 21-year-old girl, Alexis felt moved and began spontaneously to utter the words: “Holy Virgin, how I should like to believe, like all these unfortunates, that this Miraculous Spring was not but a figment of our imagination! Heal this poor girl; she has suffered so much. Grant her life, and give me faith. If this girl is healed, which seems absurd, grant that I may believe.”

The healing service began. The presiding priest urged all present to raise their hands in a petitionary gesture to heaven and beg healing from the worst disease of all—the disease of the spirit, which leads to the loss of eternal life, that is, the rejection of God and delight in sin. The priest called on all to pray for the healing of the various diseases of the body, and he appealed for total submission to the will of God.

Looking at Marie lying on the stretcher, Doctor Carrel noticed that the livid blotches on her face were beginning to fade; her cheeks began to take on a ruddy hue. He could not believe his eyes. He observed that her rapid pulse and breathing were slowing down. He felt he was witnessing an extraordinary event. Before his very eyes, the girl’s face was taking on life; the swelling of her stomach was subsiding. With every muscle of his body taut and tensed, Carrel observed the changes occurring in his parent and noted them down. Marie’s heart was beating calmly; her breathing was normal. Asked how she was feeling, she replied, “I think I have been healed.” Marie drank a glass of milk and sat up unaided. Carrel was dumbfounded. The incomprehensible had happened: here he was a witness to the instantaneous miraculous healing of a dying girl. Immediately he went to report the incident to the Medical Bureau, and then returned without delay to the hotel, to examine the cured Marie. On his way there, he saw many of the sick who had not received a physical healing and continued to suffer, being eaten up by cancer and other diseases. Yet despite this, their faces radiated a mysterious joy. Though Carrel did not realize it then, this was a sign of their spiritual healing, their reconciliation with the will of God, and their offering up of their sufferings to God for the salvation of the world.

When Carrel arrived at Marie’s bed, he was stupefied. She was seated, smiling, and healthy. “Doctor,” she exclaimed joyfully, “I am completely cured.” Carrel gave her a thorough examination. Her pulse was normal—80 beats to a minute, her body was white and smooth, her stomach flat and even like a young girl’s, with no sign of swelling or hard mass; her diaphragm was thin and supple. A complete healing! From the medical point of view this was an indisputable fact. A similar examination was conducted by the two doctors, who confirmed the total cure. All were convinced that they had witnessed a great miracle.

Conversion

The miracle to which Carrel was a witness dealt him a spiritual and intellectual shock. It brought to his awareness the existence of a reality that fell outside of sensory experience. Carrel understood that empirical scientific methods were suitable only for the study of material reality. But there existed a spiritual dimension of reality, just as real as the one known through the senses, which can be experienced only on the ground of faith. With great humility Carrel began to pray to the Blessed Mother: “You responded to my lack of faith with a great miracle. I am unable to understand what happened to my patient or to rid myself of doubts. But it is my greatest wish to believe without quibbling or caviling.”

What Carrel had until now considered absurd, had become a reality. All his previous theories had been scattered like fine dust. What a great lesson in humility this was for him! No longer did he look with pity at the praying pilgrims. Could not this prayer of theirs be a way of opening oneself up to the action of the almighty power of God Himself? But Carrel’s abrupt rejection of atheism was not so simple a matter. It unleashed a dramatic struggle in his heart. Perhaps he had been deceived or mistaken in his diagnosis? He would dismiss these thoughts, for the healing had occurred before his very eyes, like any laboratory experiment. To question this fact would be the height of dishonesty and falsehood. He drew the obvious conclusion: such healings did not occur by the forces of nature, but by the power of God. But now there was a fundamental problem. How to accept the reality of faith? How to open oneself up to this incomprehensible mystery, which lay beyond the reach of scientific inquiry? “There is no proof that God exists,” thought Carrel, “or that the Holy Virgin is but a figment of our imagination. It is difficult to prove the existence of God, but neither is it possible to deny His existence. How is it that some of our most outstanding scientists, Louis Pasteur for example, can reconcile faith in the inerrancy of science with faith in God?”

Carrel sat before the Grotto wrestling with these questions until two in the morning. In the end, he decided to enter the church, which was filled with Basque pilgrims. He knelt down beside a venerable old rustic, and, from the depths of his hurting soul, he began to pray: “Holy Virgin, refuge of the poor, you answered my lack of faith with a great miracle. I cannot comprehend it, nor can I rid myself of doubt. My greatest desire, the aim of all my aspirations, is to have an unshakable faith. Accept me, a sinner harried by his pursuit after specious lights. Beneath the hard rock of my intellectual pride there lives the most beautiful of all dreams—alas, still stifled—to believe in you and love you even as do these religious sisters of unblemished souls.” Following this prayer, Carrel felt an unimaginable sense of peace and certainty that God existed and loved him with an unconditional love. He wrote: “Since the soul inclines to God, she will find peace and abide in God, and God will abide in her. (…) God is beyond all imagining and understanding. But where reason has no access, there desire and love are admitted.”

This was the crucial moment of his life. He understood that man’s richest treasure was faith in God, who, in Jesus Christ, became a real man—faith in the supreme miracle, which was Christ’s Resurrection from the Dead. For the gift of faith we need to pray daily. Carrel believed in Christ’s real presence in the Eucharist. He believed that Jesus was God, the second Person of the Holy Trinity; that He rose from the dead and is present in the Catholic Church, teaching, healing, and freeing from slavery to sin all those who in the sacrament of penance receive the gift of His Divine Mercy.

The sign of every authentic conversion is total obedience to Christ, who loves, heals, and teaches in the Church. Alexis Carrel wrote: “I believe in everything the Catholic Church teaches. I do not find this difficult, for I see no contradiction between scientific facts and the teachings of the Church.” He acknowledged his total dependence on God. In consequence, he submitted to God’s holy will his reason, his own will, and all his actions. In Carrel’s notes of that time, the following prayer has been preserved: “Lord, guide my life, for I blunder in darkness. My God, how I regret that I understood nothing of life, seeking to understand matters that man seeks in vain to understand. Life does not depend on understanding, but rather on love, on bearing a hand to others, on prayer, on work. Grant, O my God, that I may not have discovered this too late!”

While browsing through the register of miraculous healings at the Lourdes Medical Bureau, Carrel noticed the names of physicians—many of them his friends and colleagues—who feared to admit that they had been to Lourdes. They were afraid of being ridiculed as benighted fools. The popular press of the day promoted the view that the events at Lourdes were a great fraud perpetrated on the public by the clergy. By involving himself in Lourdes affairs, Carrel also ran the risk of encountering obstacles to his scientific career. But the doctor was not daunted. Come what may, he was determined to bear witness to the truth he had discovered. With full conviction, Dr. Carrel signed the medical report detailing the instantaneous and total cure of the dying 21-year-old Marie Bailly. On returning home, he published articles on the subject in the local newspaper. Immediately following these publications, anticlerical politicians and a group of university professors attacked him in the press. Dr. Carrel’s superior informed him that after his publications about the miracle there would no place for him at the university unless he recanted everything he had written about Lourdes. But Dr. Carrel refused to yield. He would sooner sacrifice his scientific career than submit to such blackmail and renounce the truth.

Emigration

Carrel was fired from the university. A few months later, in May of 1904, he left for Canada. In 1906 her moved to New York, where at the Rockefeller Institute he soon became one of that research team’s most outstanding scientists. He conducted experiments on animals, developing new surgical techniques, which enjoyed great success. He operated on a child’s circulation system and, in doing so, saved the child’s life. The May 14, 1910 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association hailed the procedure as a landmark event. Carrel conducted experimental transplants of entire animal organs. From animal embryos, he extracted a substance that made it possible to keep tissues and organ alive outside the body. He succeeded in keeping a chicken’s heart alive for twenty years. These experiments proved to be a watershed in the field of medicine, for they laid the groundwork for human organ transplants as well as surgical procedures on the heart and the circulation system. For these achievements, in 1912, Alexis Carrel was awarded the Nobel Prize in the field of medicine and physiology.

Whenever possible, Carrel made pilgrimages to Lourdes. He traveled there to pray and give thanks for the gift of faith; but he also went as a scientist, to continue studying the mystery of the miraculous healings. In 1910, during a visit to Lourdes, Dr. Carrel witnessed the spectacular miracle of a child, blind since birth, regaining its sight. That same day, in the evening, while on his way to pray to the Grotto of Apparitions, he met a beautiful young woman. She turned out to be the volunteer caretaker of that very child whose sight had been miraculously restored. The 35-year-old Madame de la Meyrie came from an aristocratic family. After the death of her husband, she had devoted herself to charitable work and the raising of her young son. She and Carrel formed a friendship, which soon blossomed into mutual love, and culminated in their entering into holy matrimony.

After the outbreak of WWI, Carrel and his wife returned to France. They were assigned to an ambulance service unit on the front. Carrel was shocked by the barbarities he saw there. In one of his letters, he observed: “The neutral countries need to know what kind of culture the Germans are bringing to the world. The German army is committing inexcusable crimes. I am simply astounded to see how this country, for whose scientists I have the profoundest respect, unite their enormous intellectual development with a morality worthy of primitive barbarians” (June 6, 1915).

During the war Carrel witnessed a great number of deaths caused by gangrene and various infectious diseases. Seeking to address this problem, he, in association with English chemist Dr. Henry Dakin, developed a new antiseptic solution to combat infection and promote healing of wounds. This discovery, which contributed greatly to a decrease in the number of amputations, was very quickly adopted throughout the world.

After the war, Carrel returned to the Rockefeller Institute, where in 1935, after five years of collaboration with Charles Lindbergh (the famous builder and pilot, who made the first solo trans-Atlantic flight) constructed the first artificial heart capable of keeping alive organs, while these remained separated from the organism during an operation. That same year Carrel published his book L’homme cet inconnu (Man, The Unknown), which became a world bestseller.

Threshold of eternity

Carrel was convinced that modern civilization had lost its spiritual values, and therefore brought man no happiness. To protect itself from self-annihilation, humanity had to open itself up to that “Being, who was the source of all, to that power and center of strength which Christian mystics call God.” He warned: “Moral backwardness often goes hand in hand with high intelligence; as a result, the morally backward are particularly dangerous members of society. (…) Morality is an assemblage of principles which people ought to observe if they wish to survive both as individuals and as a species. (…) Believers ought to act according to Christian moral norms. Unbelievers ought also to obey these principles, for these norms are the responsibility of every human being endowed with reason and capable of reflecting on the way in which the world is organized.”

Carrel’s last book, written before his death in 1944, was devoted to the power of prayer. He observed that through prayer man enters into a personal relationship of love with God. Prayer “becomes (…) the source of the most potent life-giving energy. Those who have fostered within themselves the habit of regular, honest prayer are bound to feel that their whole life has undergone a great transformation. The habit of prayer makes an indelible imprint on all our actions and conduct. Man begins to see himself and the errors in which he finds himself yoked. He begins to feel the discomfiting growth of his self-love, the futility of this understanding, the aimlessness of his desires, the insignificance of his cares and worries. There develops in him a sense of moral responsibility and intellectual humility. Thus begins his pilgrimage to the Source of grace.”

Carrel’s total commitment to God in his life is most fully seen in his daily, persevering prayer through regular confession, frequent reception of the Eucharist and sacrificial service to his neighbor. He prepared himself for his meeting with God at the moment of death. He knew well that that moment would bring with it the judgment that determines eternity in heaven or hell. He took to heart the warning of Holy Scripture: “Do not be deceived; God is not mocked, for whatever a man sows, that he will also reap. For he who sows to his own flesh will from the flesh reap corruption; but he who sows to the Spirit will from the Spirit reap eternal life” (Ga 6: 7-8). Here is how he prayed: “Lord, guide my life, or else I lose myself in darkness. I carry out all that your will inspires in me. (…) O God, before you close the book of my life, give me access to that grace, that I may discover in it all that I do not yet know. My life has been a wilderness, for I did not know you. Grant that this wilderness many blossom forth despite the autumn of my life. May I offer up to you every moment of the days that remain to me. I ask nothing more for myself apart from your grace. May I, in your hands, become like smoke borne on the wind. Enlighten me, Lord, how to help those whom I love. Into your hands, Lord, I commend the full entirety of my nothingness.”

Carrel prepared for his death by making his confession, receiving Holy Communion and the sacrament of this sick. He departed into eternity in Paris on November 5, 1944. He understood the miraculous healings at Lourdes to which he was an eyewitness as signs calling him to conversion and pointing to the existence of the reality of God that lies beyond sensory experience. A relentless search for truth and scientific honesty prompted Alexis Carrel to reject atheism and believe in Jesus Christ.

All of us are given clear signs that we may convert and accept the gift of salvation. But these signs do not force our will. In encountering these signs, miracles, and extraordinary manifestations of God, we remain free, for in these mysterious events there is a sufficiently great number of arguments for the person of good will to believe, and a sufficiently number of counterarguments for those who do not wish to believe. Man is a free agent and can say “no” to God. But at the judgment following our death, we will not escape condemnation, if we consciously and willingly rejected the grace of faith and the gift of eternal life (cf. Rom 1: 20).

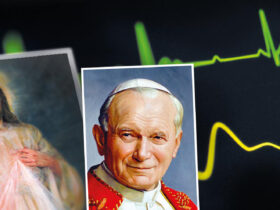

John Paul II addresses those afflicted with suffering:

“Suffering, permeated by the spirit of Christ’s sacrifice, is the irreplaceable mediator and author of the good things which are indispensable for the world’s salvation. It is suffering, more than anything else, which clears the way for the grace that transforms human souls” (Salvifici doloris, 27). Let us then offer up our weaknesses and afflictions to God and, by uniting our sufferings with those of Christ, plead graces for the whole world!

Prayer of Suffering

“Jesus, Divine Savior, through the Immaculate Heart of Mary, I offer you my physical pain and mental suffering for the intentions of Holy Mother Church, for priests, for Love One Another Magazine, for the apostolate of life (add other intentions). Pour over the world the rivers of your Mercy. Convert the unbelieving, free those enslaved to addictions. Surround all families with your loving care, that through your grace they may resist the snares of the Evil One. Unite families in danger of breakdown. Give courage and love to parents that they may accept every new life with love and protect it from the moment of conception to natural death. Give the elderly the grace of uniting themselves with you in their suffering. Grant a pure heart to children and young people, that they may be free of addictions and ready to do the Father’s will. Grant that this cross, which I bear, may become for me a source of courage, freedom, and power, that my sufferings may not deprive me of hope, that my faith may not be extinguished, that my love may never die. And when my life draws to its end, may the ministering angels console me and take me into your Kingdom. Amen.”