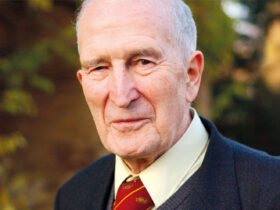

Pater from Paberžė

“Four kilometers to the bus stop, four kilometers to the phone. Poverty – poverty and loneliness … Beautiful place. Not even a party secretary nor a Komsomol member” – this is how Father Stanislovas remembered his beginnings in Paberžė (Lithuania). Throughout his life he was not afraid to clean the dust off the Gospel in churches or sweep the yard in front of his country cottage.

The Beginnings

Algirdas Mykolas Dobrovolskis was born on September 29, 1918 in the town of Radviliškis near Šiauliai in Lithuania. His father was a railroad worker. At first Algirdas studied at a local school in his hometown and then at the Jesuit College in Kaunas. In 1936 he joined the Capuchin novitiate in Plungė. He received the religious name Stanisław on the day of his investiture.

In 1941 he made his perpetual vows, and because of the fact that during his formation the young Capuchin had developed a reputation for being extremely hard-working and gifted, his superiors intended to send him to France for further studies. These plans were thwarted when the Red Army entered Lithuania in 1941 and the Soviet occupation started. In this situation, following the order of his superiors, Brother Stanislovas began his theological studies at the diocesan seminary in Kaunas. In Lithuania, the Soviet occupation soon became the German occupation. The Capuchin became involved in saving Jews. Soon, the Gestapo found evidence of his activities, and he was one step away from imprisonment in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Divine Providence, however, prevented this from happening. After Brother Stanislovas’s ordination to the priesthood on March 25, 1944, he was assigned to a monastery in Petrašiūnai (now a suburb of Kaunas) with the task of conducting missions and retreats, and preaching patronal feast day sermons.

A Zealous Preacher

In 1945 the Soviet communists from Russia re-invaded Lithuania, pushing back the German occupiers. They then closed the Capuchin monasteries in Plungė and in Šiauliai. Only the monastery in Petrašiūnai remained. In facing up to this challenge, the great mission of Father Stanislovas’s life began: traveling all over Lithuania. In a period of four and a half years, he visited nearly 100 parishes. With a shepherd’s care he helped the faithful overcome the fear, hopelessness, and terror that had been spread by the communists.

Cardinal Vincentas Sladkevičius, who was ordained a priest together with Father Stanislovas, recalls: “In Kaunas he preached very bold sermons. It was 1948, people were being taken away, and he said in one sermon: ‘Now we are praying, and at the railway station there are wagons ready and crowded with people. And these people are also praying and crying because they are leaving their homeland.’ But even when he touched on those dangerous subjects at that time, he never spoke disparagingly (about the Communists – ed. note). He accepted the blows of fate as coming from the hands of the Lord. Everything, he said, related to the current situation, but without political agitation. His words were not inciting hostility, so people came to his sermons.”

In one of his sermons, during the Second World War (1939-1945), Father Stanislovas said: “Let us be very careful in judging. There aren’t as many bad people as we think. Even if a man becomes as hard as a rock, a spark of good still glows in his heart and it is simply not always visible … Christ says in the Gospel that he will not quench a smoldering wick. (Matthew 12:20) Christ will not reject him, he will send a good man who will truly help him. If we want to be apostles, we should not extinguish this delicate light with our rough hands, we should not condemn anyone.”

Siberia

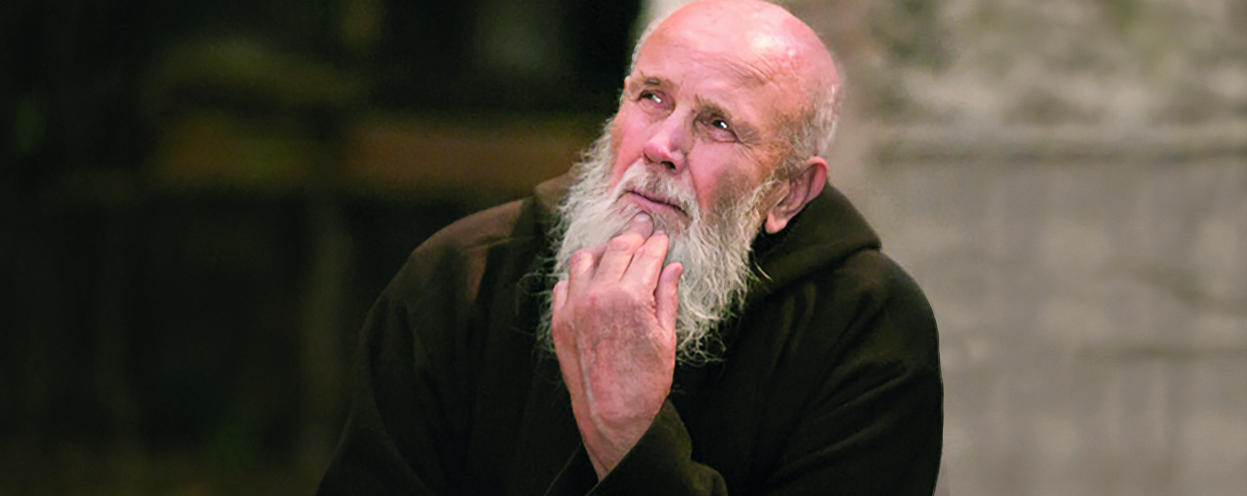

On August 11, 1948, Father Stanislovas was arrested and charged with “anti-Soviet nationalist or religious motivation.” He served eight years in a labor camp in Inta, in the Komi Republic, near the Arctic Circle. He worked in local coal mines and at construction sites. Other prisoners remembered him as a zealous priest of exceptional spiritual strength, sacrificing himself for others. He himself asked for the hardest work, shared the packages he received with others, and he still had the strength to celebrate the Eucharist and to learn Spanish. When he was released in August 1956, he was asked by the commander if he had changed his beliefs, the Capuchin replied: “Beliefs do not change, citizen commandant, they deepen.” After returning to Lithuania, the Capuchin priest was sent to the tiny rural parish of Vertimai in the Jurbarkas region.

In March 1957, Father Stanislovas was arrested again for “proclaiming anti-state views,” and again imprisoned in a camp – this time in Vorkuta (also Komi Republic). This imprisonment lasted several months. This is what the Capuchin said about the years he spent at the camps: “I sang in the mine, feeling glad that I was alive. I have a retirement pension of 139 litas (about 40 euros – ed. note). Don’t you dare give me a prisoner’s pension! It is an honor for me to have been a prisoner in Siberia.” Father Stanislovas was convinced that thanks to his imprisonment in the camps, God saved him from “youthful fantasies and romantic, empty dreams.” He could see God’s gift in these terrible experiences.

Restrictions

When the Capuchin returned from his second imprisonment, the authorities even banned him from wearing a habit and a beard. In the period that fallowed, Father Stanislovas was often transferred to the smallest and poorest Lithuanian parishes: Juodeikiai, Žemaitkiemis, Milašaičiai, and Butkiškė. Deprived of basic living conditions, he slept in the sacristy of churches. In Žemaitkiemis, he was not even permitted to perform his priestly duties. This period, which lasted a year and a half, Father Stanislovas found to be worse than the camp. He found solace in hard physical work and in the translation of poetry: on his own initiative the Capuchin cleaned and put things in order around the town and surrounding areas.

In the summer of 1961, Father Stanislovas was restored to the priesthood and transferred to Milašaičiai. During the period when he was suspended from pastoral work, he had also devoted himself to philosophical and theological studies. The priest ordered books written by famous foreign authors from the Russian National Library in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and he translated them into Lithuanian (he knew eight foreign languages).

Paberžė

Father Stanislovas served in Paberžė from 1966 to 1990. Thanks to his efforts, the reconstructed village quickly became a place which attracted people who were thirsty for God and spiritual consolation. They came not only from all over Lithuania, but also from other parts. Believers came to Father Stanislovas asking for baptisms, weddings, First Communions, or funerals. People who were depressed and thirsty for consolation, alcoholics and drug addicts, as well as oppositionists, also came there to simply stay in his presence and draw from the strength of his spirit. The Capuchin’s modest lifestyle, his deep prayer life, and hospitality and hard physical work, which Father Stanislovas never avoided, impressed many. The Capuchin father had a gift for attentively and sincerely listening to both the oppressed, who had come from poor villages, and the intellectuals. “Pater” (Latin for father) – as Father Stanislovas was called – knew “how to talk both to a peasant and to a philosopher.”

Father Stanislovas also kept illegal underground literature (including the works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn), his own translations of the works of foreign authors, and Lithuanian books from before the Soviet occupation. He distributed these all over Lithuania. Soviet security officers also constantly “visited” him. They often searched the presbytery and church in Paberžė. Sometimes the Capuchin priest’s personal notes, sermons, and translations of foreign authors were confiscated. Father Stanisław accepted all of this with stoic calm. He always talked calmly to the KGB, and he converted many of them. New ones came to replace the converts.

Respect and Mental Hygiene

On one occasion, Pater went to Vilnius to meet with the so called “converts” – as those who had been won over for Christ by the Capuchin’s word and example were called. First, he walked with them for a long time, and then always went to the same cafe. There, the “converts” had their “exam”. They sat together and drank coffee, and then Pater collected their saucers, plates, cups, and spoons to help the staff. A certain neophyte, passionately sharing his deeply felt spiritual problems, pulled Father away at one point, saying, “Please stop, she will clean up!” At the end of the walk, Pater addressed that man: “My beloved! You don’t have to go to church if you think that way because you will be imitating the Pharisees and they killed Christ. It is not good. Please learn how to clean up the table after yourself, take others into account and listen to them!”

Olga Yerokhina, a parishioner of Father Alexander Men’s from Moscow, recalls: “Pater talked about mental hygiene: ‘You know, there is this one atrocity: Muscovites babble and babble. Moscow lives a terrible rhythm. You should rather seek and love silence – and believe me, believe me – God will reveal himself to you. When? It’s not your business or mine. It sometimes happens before death. But don’t give up prayer, please. You have to write down the words. Of the ten words you want to say, say two and write down the rest – write down what is in excess. Do not get involved in everything and do not forget: salvation – in Latin salvatio – means health.’”

The Battle for Souls

With his prayer, word, and example, Father Stanislovas, freed his charges “from the yoke of the spiritual occupier.” Many people, having lived with Pater for some time, came back to life and to society.

One of the ways of “purifying lost souls” – as an ascetic practice – was scrubbing Father Stanislovas’s copper pots until they shone, and forging “suns” – Lithuanian crosses, which the father later handed out to his guests.

Pray and Work

In 1990, Father Stanislovas was transferred to Dotnuva, where he renovated the post-Bernardine church and monastery. He was 72 years old then. He could feel the aches of the years spent in the camp as well as the persecutions that he experienced, but the strength of his spirit was still inexhaustible. In addition, he was accused of “liking the Bolsheviks.” He was often visited by former communists. The Capuchin always talked with everyone he met, without making any distinctions.

Father Stanislovas did not lack pastoral work. He served parishioners not only in Dotnuva, but also in Paberžė. Believers from all over Lithuania also came to him. He used to say, “I don’t know what it means to do nothing … The joy of the work done is a sweet yoke.”

After Lithuania regained independence, and censorship was lifted, Father Stanislovas’s sermons began to be printed and distributed in magazines and books. Here is an excerpt from one of them (from 1994): “In the evening, when worries begin to bite you and it turns out that your heart is no longer able to bear it, try this old reliable method: kneel at the bed or at the table, put your head in your hands and pray. If words get stuck in your throat – cry and sob. If crying doesn’t help, then keep quiet. Meditate in silence until you feel everything sinking to the bottom … Seeing a man burdened with concern, stop, take your time, and repeat the words the Lord said: ‘Why are you sad?’” (Luke 24:17)

“There is a Disease – But the Patient is Missing”

In 2002, due to advanced cancer, Father Stanislovas returned from Dotnuva to Paberžė. Despite his weaknesses, he did not give up his pastoral ministry. When he came back from the hospital, he said that although “there is a disease – there is no patient.” He stoically accepted his physical ailments. At that time, as in previous years, Paberžė became a haven for alcoholics, drug addicts, and all who could not find their way through the hardships of life.

During the consecration at the last Holy Mass which he celebrated on June 5, 2005 in Paberžė, Father Stanislovas fainted. He grabbed his head, took a sip of the water he was given, and exclaimed: “God, save our homeland! Send your help, oh Lord … What can I tell you about the disease today? Don’t just be sick in your bones; embrace it in your being. The disease is a great trial not only for the body. Wake up with a prayer on your lips. In life, we often immerse ourselves in the desires of the body so that we become only the body and the soul disappears. Let the soul break free from the bondage of bodily desires … Go with God. Choristers, what do you have there that is good? Sing. I’m leaving. It’s enough – 87 years. You go but I am staying.” There was suffering showing on Father Stanisław’s face. People were crying, coming up to him asking for the last blessing. Finally, Pater asked to be left alone in the church. He died in a hospital in Kaunas on June 23, 2005, and was buried in the courtyard of the church in his beloved Paberžė.

Miracles and Favors

Now, several years after the death of the Capuchin, there is no shortage of pilgrims in Paberžė. Those who remember Father Stanislovas and those who experienced the grace of faith through him gather on the 23rd of each month. People write letters about healings through his intercession. Father Gintaras Vincentas Tamošauskas, O.F.M. Cap talks about the healing of the exorcist Father Arnoldas Valkauskas. His body was suffering severe infection. When Arnoldas prayed at the grave of Father Stanislovas, he was immediately healed. According to Father Vincentas, there are many other stories like this one: “While (Pater) was still alive, a depressed woman called him. He prayed for her and her depression disappeared.”

The fact that the cult of Father Stanislovas is alive is also evidenced by the existence of the Father Stanislovas Association, with a current membership of 200 people, who are praying for Lithuania and cultivating the memory of the Capuchin Father. The Father Stanislovas Spirituality Center, which organizes retreats and other events in Lithuania is also being established. In addition, the religious authorities of the Cracow province of Capuchins have decided to collect materials and testimonies focusing on the beginning of Father Stanisław’s beatification process.

Do you like the content published on our website?

Support us!