“My Lord and my God!” (Jn 20: 28)

Since the dogma of the Holy Trinity escapes rational understanding, it raises natural barriers to any thinking person. Who thought it up and why? Would it not be easier to believe that God is One and not to delve into the question of whether or not He constitutes three persons? No question: it would be easier, but would it be honest with respect to God, who revealed to us the truth about Himself?

The Jews have a saying that any Jew can fall into sin, disbelief, or even apostasy; but a Jew would have to be mad to acknowledge another Jew as God. This conviction is directly linked with the history of Biblical Revelation, in which the severely tested Jewish people had to learn to distinguish the Truth about God from the truth about man. Every Jew knows full well who God is and who man is. And every Jew knows full well that neither could God be a man, nor could a man be God. Here we need to ask ourselves several questions: Did Jesus consider Himself God? Did the apostles (Jews to the core) consider Jesus God? Who began to consider Jesus as God—and when in the history of the Church did this begin?

Conviction in the divinity of Jesus—early second century A.D.

Few would question the fact that there existed in the Church of the early second century a general conviction in the divinity of Jesus. The proofs of this are many, and the evidence is “hard”—irrefutable. I will adduce only four pieces of evidence—the most compelling ones.

First of all, there is the well-known Rylands papyrus designated as P52. This tiny fragment of papyrus is inscribed on both sides with Greek letters. The letters conform to verses 31-33 and 37-38 of Chapter 18 of the Gospel according to John. They describe the trial of Jesus, which would have made no sense without reference to His divinity: “The Jews answered him, ‘We have a law, and by that law he ought to die, because he has made himself the Son of God’” (Jn 19: 7). Knowing that the Rylands papyrus dates from around 120 A.D, we must accept that the Gospel of John with all its claims as to the divinity of Jesus was known and read in the Church in the 20s of the second century.

The second papyrus, of no less moment, is the one designated as P90. It comes from another codex of St. John’s Gospel also dating from the second century. It is true that P90 has been ascribed to the early third century, but in the light of the most recent research carried out on fresh discoveries, Dr. C. P. Thiede dates the writing of this text to a considerably earlier period. This fragment of papyrus contains excerpts conforming to 18: 36 – 19: 7 of John’s Gospel, thus confirming that already then there was present in the Gospel text the above-cited verse (19: 7). It was not added later.

The third piece of evidence are the letters of Pliny the Younger, an imperial Roman functionary and governor of Bithynia-Pontus who, between 110 and 112, wrote 247 letters. These letters, well known to scholars, have been numerated and throroughly studied. In Letter 96, Pliny wrote: “the whole of their [the Christians’] guilt, or their error, was, that they were in the habit of meeting on a certain fixed day before it was light, when they sang in alternate verses a hymn to Christ, as to a god.”

Needless to say, Pliny was not a Christian. Since he was a rationalist, like any Roman, he considered the Church’s claim that Jesus was God preposterous. Nevertheless, his letter confirms that at that time, between 110 and 112, the Christians universally worshiped Jesus as God.

The fourth piece of evidence dating from the early second century are the letters of St. Ignatius, bishop of Antioch. Ignatius acceded to the antiochian bishopric at approximately 69 A.D. He must have known most of the apostles personally. Tradition has it that he was one of the disciples of John the Apostle. Arrested in 107 and transported to Rome for execution, Ignatius asked the Roman authorities if he might meet with Christians along the way. The Romans granted him his wish, and thus this remarkable man, in the face of certain death, found the words to console his brethren and strengthen their faith in Jesus Christ. On his way to Rome, Ignatius wrote seven letters, each of them beginning with the words: “Ignatius who called Theophor,” which means “he who bears God”—i.e. proclaims Him and His teaching. These letters contain expressions of his belief in the divinity and humanity of Christ as well as the universal mission of the Church, which, for the first time, he called “catholic.”

Since Ignatius of Antioch was not a Jew, some scholars have been tempted to lay upon him the responsibility of attributing divinity to Jesus. But the honest scholar must acknowledge the fact that as the third bishop of Antioch (after Sts. Peter and Evodius) and as a disciple of John the Apostle, Ignatius could hardly have come up with some random dogma of his own—especially since he was proclaiming this Truth of the divinity of Jesus while confronting death, a time when man revises all his current views and speaks only of what he is certain.

Nomina sacra—God’s abbreviated names

The fact that Jesus was identified with God even in apostolic times (i.e. in the lifetime of His first disciples) is seen in the abbreviated names of God used in the papyri. Scholars call these abbreviations nomina sacra—sacred names.

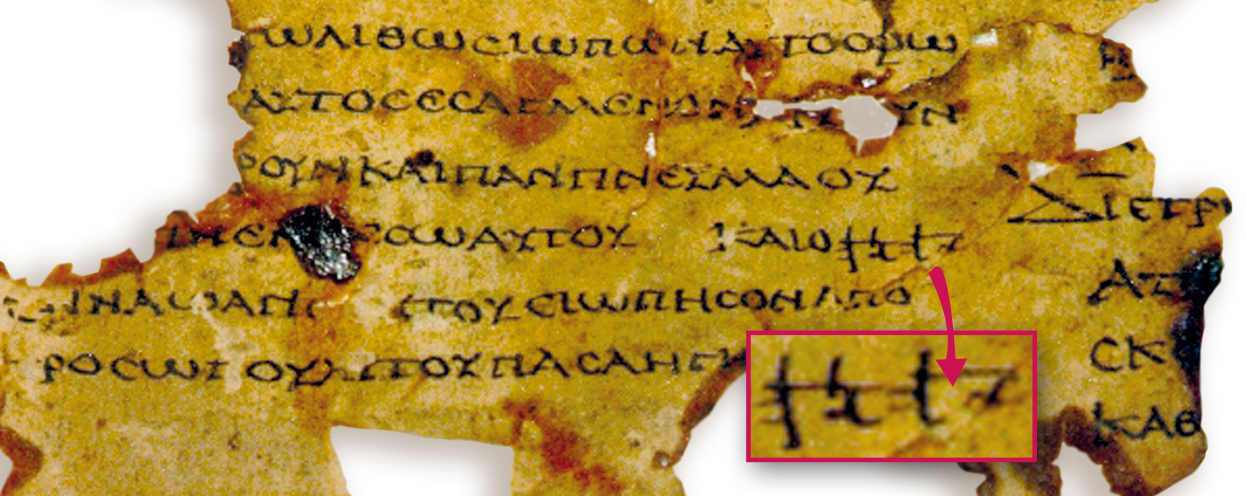

This use of special symbols denoting the name of God in sacred writings was characteristic of Judaism and the Jewish mentality. It is well known that the Jews uttered God’s name only on the grounds of the Temple. In the time of Jesus, no one vocalized it except for the chief priest, and this but once a year on the Feast of Propitiation (Yom Kippur). Consequently, in their daily reading of Holy Scripture, or while praying, the Jews had to replace the Name of God with another word, e.g. Hashem (“Name”) or Adonai (“Lord”). To prevent the accidental utterance of the Name, the sacred texts clearly highlighted the tetagram YHWH denoting the Name of God. A different alphabet was used, as is seen in the documents illustrated above. Both in the Hebrew texts, written in its characteristic “square” letters, and in the Greek texts, the tetagram YHWH was inscribed in the ancient Hebrew alphabet, which had been used in the times prior to the Babylonian Exile. Anyone reading these texts aloud would automatically substitute for the Name of God the words Hashem or Adonai.

Thanks to this notation it was immediately clear, especially in Greek manuscripts, to which “lord” the given word kyrios or adonai referred: to man or to God. The nomina sacra used in Greek Christian manuscripts performed an identical function. The word kyrios written out in full would mean “any lord whatever,” while the abbreviation KS would denote only God or Jesus. Similarly the word theos, would denote any god (cf. Acts 14: 11 or 1 Cor 8: 5). By contrast the notation ThS referred only, and exclusively, to God.

The usage of abbreviated nomina sacra was a Jewish idea through and through, stemming from the need felt in the first century to highlight the Name of God in writing. If the nomina sacra were introduced in apostolic times, this indicated that the apostles acknowledged Jesus as God, since the abbreviations KS and ThS in the manuscripts are also used in reference to Jesus.

Scholars have at their disposal a great number of papyri, which by comparing the different ways of forming the letters, can be dated quite accurately. For example, on July 24, 66 A.D, an Egyptian peasant by the name of Harmijsis wrote a petition in Greek concerning the purchase of seven sheep. This event had little historical significance in the year 66, but it has great significance for us today, for the document indicates the date of writing and shows the signatures of three government officials. This papyrus languished in the earth until recent times when it was discovered during excavations at Oxyrhynchos, together with hundreds of other papyri.

The writing style of Harmijsis’ petition (needless to say, it was set down by a literate scribe) is the same as that apparent in papyri P64/67. (This was discussed at greater length in issue nineteen of LOA.) This indicates that they were written in the same period by scribes using the same caligraphic principles. This enables us to date P64/67 to the late 60s of the first century. Moreover, there are extant several ostraca (potsherds used as writing surfaces) from Masada that recall the writing style of papyri P64/65 (in particular, item #784). That Masada has not been inhabited since the year 73 is a matter of historical record.

We come to the most important conclusion deriving from our knowledge of the papyri and nomina sacra. Papyrus P64, which we know to have been written in the 60s of the first century, when almost all the apostles were still living, indicates the abbreviated notation KE in place of kyrie in Mt 26: 22 and IS in place of iesous in Mt 26: 31. This is the earliest instance of using abbreviated nomina sacra. Papyrus 7Q4, originating prior to the year 60, contains the word theos written out in full. This means that sacra nomina were introduced into Christian texts in the mid-60s of the first century, during the lifetime of most of the apostles, and that these implied their belief in the divinity of Jesus. From then on, we begin to encounter papyri in which, for example, the abbreviation ThS appears in reference to Jesus, as in the Gospel of John l: 1 (papyrus P66—possible date: approximately 125) and the respective abbreviations of underlined words in the Letter to the Philippians 2: 6-7 (papyrus P46—possible date: approximately 85): “Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped.”

The copies of the New Testament highlight in writing the references to Jesus as God, and this in the lifetime of the apostles, including the authors of the Gospels and Epistles. In the Jewish mentality this implied a belief in Jesus as God.

Did Jesus consider Himself God?

In the light of the great number of papyri dating from the second century and the few extant fragments of first century texts that conform exactly to the New Testament as we know it, we must accept the fact that the Gospels and apostolic letters as copied and read in the Church in the lifetime of the apostles and other eyewitnesses did not differ substantially from the versions we have today. The available scientific evidence makes untenable the hypothesis that verses were deleted from and added to these documents at a later time. Every reader of the New Testament who has even a passing knowledge of the Old Testament immediately notices that Jesus’ utterances constantly allude to his equality with God. The table shown above includes several of the clearest statements in which Jesus sets Himself in the place of God.

Even such a classic text as the Sermon on the Mount provides proof that Jesus considered Himself God. According to Rabbi James Neusner, almost every sentence of the Sermon on the Mount defines the Person of Jesus rather than introducing a new moral principle. In his book A Rabbi Talks with Jesus, Neusner writes: “Here comes a teacher of the Torah, who says in his own behalf what the Torah says in the name of God.” Indeed, all of Jesus’ utterances in the cultural-religious context of Judaism point exactly to what we believe: that He was God.

From the Jewish standpoint, such claims were blasphemous. Man may never compare himself with God. The Jews often had issues with the Romans, when the latter acknowledged their Caesar as God. The Jew would have died rather than utter such a blasphemy. That is also why the reaction of the Jews toward Jesus was so consistent: “the Jews sought all the more to kill him, because he not only broke the sabbath but also called God his Father, making himself equal with God” (Jn 5: 18). Whoever made himself equal to God, had to suffer death (cf. Acts 12: 22-23).

This is also what made Jesus’ trial the most bizarre trial on earth. He was condemned not for what He did, but for Who He was: “Again the high priest asked him, ‘Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?’ And Jesus said, ‘I am; and you will see the Son of man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.” And the high priest tore his garments, and said, “Why do we still need witnesses? You have heard his blasphemy’” (Mk 14: 61-63).

The Sanhedrin’s decision to have Jesus crucified can only mean that the Jews correctly understood His utterances as to His own divinity. Jesus must have been convinced that He was God, since He allowed Himself to be killed for this conviction alone.

The Apostles change their minds

Let us return to the question posed earlier. Is it possible that a Jew began suddenly to consider another Jew as God? Consider the convictions of Jesus’ apostles.

In the Gospels we encounter several places where Jesus’ supporters and disciples are clearly disturbed and forced to ask themselves as His identity. The simplest example is the calming of the storm. We have grown so used to it that we rarely stop to think that this was an event that totally upset the Jewish notion of the Messiah.

Matthew the Evangelist writes: “And the men marveled, saying, ‘What sort of man is this, that even winds and sea obey him?’” (Matt 8: 27). The point is that anyone can speak of his equality with the Father. Anyone can set himself in the place of the Lord of the Sabbath (i.e. God who established the Sabbath). But only God can calm a storm. “At their wits’ end (…) they cried to the LORD in their trouble, and he delivered them from their distress; he made the storm be still, and the waves of the sea were hushed” (Ps 107: 28-29). In this instance, Jesus did not have to say anything about Himself. It was enough that He had calmed the storm and asked the disciples where their faith was. Faith in what? Faith in That Which He was. No talk necessary. The deed had spoken for itself; and the apostles had to change their way of thinking under the weight of the evidence.

The most compelling instance of a change of mind is the one recorded in the Gospel of John in the example of the Apostle Thomas. We read: “Thomas answered him, ‘My Lord and my God!’” (Jn 20: 28). Did this mean anything special? Some have tried to break up his utterance, as though “Lord” referred to Jesus, and “God” to God the Father. But the problem lies in the fact that Thomas was a Jew. A Jew in such situations would say: “O Lord our God” (Adonai Eloheynu). But Thomas said, “My Lord and my God (Adonai veElohai), which clearly implies that this utterance referred to Jesus, whom Thomas had just touched.

So as not to multiply examples, one need only remind the reader that Rabbi Saul of Tarsus participated in the stoning of the deacon Stephen—and this precisely because he considered his words about Jesus standing at the right hand of the Father to be a blasphemy. A few years later, this same Rabbi Saul wrote about Jesus being “in the form of God” (i.e. that He was God), but had condescended to become a man (Phil 2: 6-7). Those of malicious mind would say he had gone mad. But Rabbi Saul simply had to change his conviction under the weight of the evidence of Jesus’ divinity. In the same way, all Jesus’ apostles and disciples had had to acknowledge Jesus as God. Quite simply, He had left them no other option.

Are there two Gods?

Why did none of the Jewish apostles, or even Rabbi Saul of Tarsus, engage Jesus in an argument as to God being, and having to be, One? All knew that the Torah stated, “Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God is one LORD” (Dt 6: 4).

The fact is that the Hebrew word used here—echad (“one”)—does not at all mean “single,” “indivisible.” Even today, the daily Jewish prayer uses the phrase goy echad (“one people”), referring to the whole nation of Israel. It never occurs to one to question the fact that the Jewish people consists of several million persons, simply on the basis of the word echad. In the same way, the phrase Adonai echad does not necessarily eliminate two persons of the Holy Trinity. What’s more, once a week the Jewish family intones the song of greeting the Sabbath, in which appears the phrase “Shamor vezachor bedibur echad” (“Observe” and “recall” in a single word). The phrase refers to the commandment about the Sabbath, beginning with the word “recall” (in Ex 20: 8) and “observe” (in Dt 5: 12). Every rabbi knows that this is an instance of “two in one.” And no one is bothered by the word echad, since it does not really mean “single.” Jesus’ Jewish apostles had to have known this. Thus the belief in the divinity of Jesus did seem to them contradictory to the fundamental truth of Judaism, which they had known from childhood.

Besides this, the Hebrew Bible (not to mention the Greek translation of the Old Testament) contains numerous suggestions identifying the Messiah with God. One of the strangest of these is found in the Book of Zechariah, which states in this rendering recognized by rabbis: “when they look on him whom they have pierced, they shall mourn for him, as one mourns for an only child, and weep bitterly over him, as one weeps over a first-born” (Zech 12: 10). These are the words of God, who clearly identifies Himself with “the one they have pierced.” Another example can be seen in the famous prophecy: “For to us a child is born, to us a son is given; and the government will be upon his shoulder, and his name will be called ‘Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace’” (Is 9: 5). This prophecy presents a huge problem in the name “Mighty God,” since this is not a name normally given to any child. In the Hebrew, El Gibor is not a name in which God is merely evoked (cf. the names Elias, Eliezar, and Elizeus). Rather it is a name referring to God Himself like El Elyon, El Shaddai, and others. Isaiah clearly foretells that the Child (Messiah) will receive the name of God, i.e. will be called God, which, in the Jewish understanding, means that He will be God.

To us, it seems paradoxical that Jesus is God and yet is not identified with the Person of God the Father. On numerous occasions, Jesus, who proved to His disciples that He was God, turns to God the Father: “And Jesus lifted up his eyes and said, ‘Father, I thank thee that thou hast heard me’” (Jn 11: 41); “And he said, ‘Abba, Father, all things are possible to thee; remove this cup from me; yet not what I will, but what thou wilt’” (Mk 14: 36).

Likewise, John the Evangelist, in speaking about God, points to the difference between Jesus and God the Father (Jn 1: 1; 1: 18, et al.). Thus, the Apostles proclaimed faith in the divinity of Jesus—the Eternal Word. Although they did not use the philosophical and theological terminology of today, their belief in the Holy Trinity was the same as is now taught by the Church.

Summary

The Divine nature and the human nature are united in the one Divine Person of the Word. Jesus considered Himself God and did all in His power that the Jews around Him might understand this. They understood Him very well. Some considered this blasphemy and condemned Jesus; others had to revise their current views.

The Apostles gave expression to their faith in the divinity of Jesus by their use, among other things, of nomina sacra. In the Jewish context, the utterances of Jesus, which they set down in writing, clearly defined Him as God. By the end of the first century, John the Evangelist called Jesus God outright, and faith in the Holy Trinity was already well documented at the beginning of the second century.

These facts should be enough to enable any one of us to believe that Jesus is both God and man, that His Divinity is the same as the Divinity of God the Father, even though He is a separate person. Even if we cannot understand this, plain logic bids us to acknowledge that Jesus not only considered Himself God, but also convinced all His disciples that He was indeed God.

“This is the antichrist, he who denies the Father and the Son. No one who denies the Son has the Father He who confesses the Son has the Father also.” (1 Jn 2: 22-23)