From Shadows and Images to the Truth The Conversion of J. H. Newman

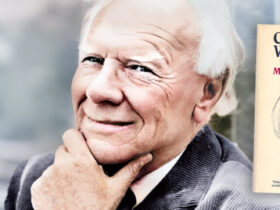

On September 18, 2010, the Holy Father Benedict XVI beatified Cardinal J. H. Newman, one of the most famous converts in the history of the Church. Newman was at once an intellectual and spiritual genius and a man of deep and humble faith. His philosophical and theological writings belong to humanity’s greatest treasures.

Blessed Cardinal John Henry Newman was born on February 24, 1801 in London, on Old Broad Street. His father was a banker; his mother came from an émigré French Huguenot family. John Henry was the oldest of six siblings (he had two brothers and three sisters). From their mother and grandmother, the children learned a simple, trusting piety. John Henry recalled that he was encouraged to read Holy Scripture daily, but until the age of fifteen he had no religious convictions.

Crisis of faith and first conversion

Extraordinarily gifted, he was raised by his father in a spirit of liberal Anglicanism. At the age of fourteen, he came across books that questioned the credibility of the Sacred Scriptures, vilified the Church, and denied the existence of miracles and the immortality of the soul. As a result of reading these anti-Christian works, the fifteen-year-old John Henry stopped believing in God. In autumn of 1816, a radical transformation took place in the boy’s life. He met a brilliant Anglican preacher who supplied him with good books. From reading these, he overcame his crisis of faith; he came to believe in the immortal soul. He no longer doubted the existence of a transcendental God who spoke through man’s conscience and on whom man’s salvation depended. But, alas, his reading of anti-Catholic Protestant authors persuaded him that the Pope was the Anti-Christ, and that the Catholic Church was a degenerate community rife with superstition.

After his conversion, the fifteen-year-old Newman professed a private vow of celibacy. He became a frequent communicant, prayed daily, fostered his awareness of God’s presence, meditated on Holy Scripture, waged a tireless struggle against pride, vanity, sexual temptation, and kept his emotions and temperament in check.

Abhorrence of sin

While growing up, J. H. Newman experienced strong temptations requiring a vigorous struggle on his part. He wrote: “Men of this world, carnal men, unbelieving men, do not believe that the temptations which they themselves experience and to which they yield, can be overcome. They reason themselves into the notion that to sin is their very nature, and, therefore, is no fault of theirs; that is, they deny the existence of sin.” Newman knew well that sin was man’s greatest tragedy. No one could walk in the way of faith to perfect happiness in heaven unless at the very outset of this journey he despised sin. That is why Newman prayed as follows: “Why didst Thou create us, but to make us happy? Couldest Thou be made more happy by creating us? and how could we be happy but in obeying Thee? Yet we determined not to be happy as Thou wouldest have us happy, but to find out a happiness of our own; and so we left Thee. O my God, what a return is it that we—that I—make Thee when we sin! what dreadful unthankfulness is it! and what will be my punishment for refusing to be happy, and for preferring hell to heaven! I know what the punishment will be; Thou wilt say, ‘Let him have it all his own way. He wishes to perish; let him perish. He despises the graces I give him; they shall turn to a curse.’ Thou, O my God, hast a claim on me, and I am wholly Thine! Thou art the Almighty Creator, and I am Thy workmanship. I am the work of Thy Hands, and Thou art my owner….and my one duty is to serve Thee. O my God, I confess that before now I have utterly forgotten this, and that I am continually forgetting it! I have acted many a time as if I were my own master, and turned from Thee rebelliously. I have acted according to my own pleasure, not according to Thine. And so far have I hardened myself, as not to feel as I ought how evil this is. I do not understand how dreadful sin is—and I do not hate it, and fear it, as I ought. I have no horror of it, or loathing. I do not turn from it with indignation, as being an insult to Thee, but I trifle with it, and, even if I do not commit great sins, I have no great reluctance to do small ones. O my God, what a great and awful difference is there between what I am and what I ought to be!”

J. H. Newman prayed to be able to despise sin. Every day he undertook the labor of scaling the path that leads to the summit of pure love and holiness. He was obedient to the voice of his conscience, which he took to be the voice of God Himself. “As from a multitude of instinctive perceptions (…) we generalize the notion of an external world (…) so from the perceptive power which identifies the intimations of conscience with the reverberations or echoes (so to say) of an external admonition, we proceed on to the notion of a Supreme Ruler and Judge, and then again we image Him and His attributes in those recurring intimations, out of which, as mental phenomena, our recognition of His existence was originally gained.”

Thirst for the truth

Newman was uncompromising in his search for the truth. He wrote: “With all my heart I thirst for the truth, and I embrace it wherever I find it.” In 1817 he began his studies at Oxford. For the first four years he read literature, mathematics, and law; later he studied Anglican theology. In 1822, his extraordinary abilities earned him an appointment as professor of theology at Oriel College. On May 29, 1825, Pentecost Sunday, he was ordained a priest in the Anglican Church. In 1828 his beloved nineteen-year-old sister Mary died suddenly. The event was one of young Newman’s most painful experiences, bringing home to him a sense of the fragility of earthly life and pointing him in the direction of eternity. He realized that moral and spiritual perfection—in a word, holiness—were far more important than intellectual excellence.

In December of 1832, Newman embarked on a long voyage to Spain, Gibraltar, Algeria, Malta, Sicily, Naples, and Rome. He reached the Eternal City on March 2, 1833. The sight of the Roman churches and the wealth of art and architecture brought Newman to his knees. On his return journey, during a stop in the breathlessly beautiful port of Bonifacio, Newman wrote his poem, The Pillar of the Cloud, which became a universally sung church hymn (“Lead, kindly Light…”). The work expressed his sense of the frailty of life and his desire to commit himself into the hands of a merciful God. He wrote: “If we do not love God, this comes from our not desiring to love Him, from our not striving to love Him, from our never praying to love Him. It means that we have never daily carried this thought and desire in our hearts; that we have never held Him constantly before our eyes in the simple events of our everyday lives. It is a matter of wanting to know our Creator; of that impulse of the heart to serve Him, which precedes a religious conversion.”

The pillar and ground of truth

Shortly after his return from Rome, in July of 1833, together with his colleagues John Keble, Edward Pusey, and Richard Froude, Newman initiated the renewal movement of the Anglican Church known as the Oxford Movement. Newman became its de facto leader. One of the main goals of this movement was to free the Church from its dependence on the state and to combat the spirit of liberalism, which was undermining the Christian faith by its questioning of objective Revealed Truth. The doctrine of the Anglican Church was set out in the official schema of the Thirty-Three Articles, formulated in the sixteenth century early in the reign of Elizabeth I. The movement sought to renew Anglicanism and restore it to its Catholic roots. Seeking to show the Catholic face of the Anglican Church, Newman published his Tract 90 in the London Times. Published in February of 1841, the article argued that the Thirty-Three Articles did not contradict Catholic doctrine.

The publication of Tract 90 resulted in numerous defections to the Catholic Church. The university authorities strongly condemned the tract, citing the author’s insincerity in attempting to reconcile the Thirty-Nine Articles with “Romanist errors.” In their pastoral letters, the bishop of Oxford and other Anglican bishops vigorously attacked Newman’s position. He became the object of a concerted smear campaign mounted in the press by Anglican clerics and university liberals.

What proved decisive in Newman’s discovery of the truth was his study of early Church history and the writings of the Church Fathers. Newman became convinced that there was a great similarity between the atmosphere that gave rise to the Arian heresy in the first centuries of Christianity and the one that fostered liberalism in the Anglican Church. Discovering the truth about the Early Church, Newman observed: “Deep down I always thought that there had to exist something greater than the English State Church and that this ‘greater something’ was founded on the Catholic and Apostolic Church of the first centuries.”

Newman received the moral certainty that the Anglican Church was in schism and that it was the Roman Catholic community that represented the Church of the apostles. His conscience clearly told him that his place was in the Roman Catholic Church. Only there could he be saved. At the same time he felt considerable apprehension. He mastered these fears through patient waiting, an intense life of prayer, penance, and study. Every day he devoted four and a half hours to prayer, and nine to study. During Lent he practiced a severe regime of fasting and abstinence. On Wednesdays and Fridays he accepted no food and read no newspapers until six o’clock in the evening. All this time he continued receiving numerous letters from friends who warned him against the terrible consequences of entering the Catholic Church.

Newman resigned from his teaching position at the university. He removed himself to the quiet of his parish in Littlemore, where he led a monastic life. There, for six years, he prepared himself for his final decision to join the community of the Catholic Church. He described this period of spiritual struggle in his book Apologia Pro Vita Sua. In September of 1843, in Littlemore, he gave his last sermon in the Anglican Church. In taking leave of the Church of his childhood, he had also to leave the university milieu of Oxford, of which he writes: “Of all earthly things, I suppose Oxford is dearest to my heart.” For Newman this was a particularly painful experience.

Toward the end of 1844, he began to write his philosophical treatise on the theory of the development of Christian doctrine. As he entered more deeply into his study of the Church Fathers, Newman came to the sure conclusion that the Church of the first centuries had endured in its unaltered form only in the Roman Catholic Church. Only there had the divine deposit of faith been preserved in its entirety. He avowed: “Through my study of the disputes in the early Church, there matured in my mind the clear conviction that it is we, Anglicans, who were the heretics.”

Newman, the greatest Anglican theologian, gave up a brilliant academic career and the comfortable posts of professor and parish vicar so as to become a member of the Catholic Church, which had been ruthlessly persecuted in England since the times of Henry VIII. In nineteenth century England, Catholics were treated as second-class citizens. Thus Newman’s decision to enter the Catholic Church came with a host of very painful consequences: the loss of a means of livelihood, a place of residence, friends, and social prestige.

On October 18, 1845, Newman threw himself at the feet of Blessed Dominic Barbieri, an Italian Passionist, and begged for his blessing, a confession, and permission to be received into the Catholic Church. Within a few years of this event, several hundred outstanding university professors followed in his footsteps. They gave up their academic careers, professorial chairs, and parish functions. Newman’s conversion was a great shock for England and the world. Hundreds of Anglican clerics and influential laymen followed his example; after the publication of Newman’s book On the Development of Christian Doctrine, the number grew to several thousands.

In his inspired sermons and writings, Newman stressed that the Church was “the pillar and ground of truth” (1 Tim 3: 15) and that the way to knowing Christ led through the living Catholic Church, which was the Church of Christ, the spiritual heir of the Early Church. He understood the Church as a community in which Christ continued to live, act, and teach. He knew that as a member of this community of the Church he must submit his conscience, intellect, and emotions to the guidance and teaching of Jesus Christ. Subjective conscience, intellect, and emotions were not the final arbiters. Above all one had to submit to the authority of Christ who was present and taught in the Church. Newman explained the truth of the infallibility of the Church and her Pontiff, the Pope, as follows: “The Gospel is a real message from heaven, which is guarded and preserved in the community of the Catholic Church.” This revealed message was entrusted to the Church and “the Church is inerrant in so far as this message is entrusted to her. For, how is one to understand inerrancy in teaching if not by affirming that the teacher is protected from error in his teaching….If the Pope is infallible, he is so only because he stands at the head of the Church, which is infallible.”

Ever since I became a Catholic

“Ever since I became a Catholic—wrote Newman—I have lived in perfect tranquility and untroubled inner peace… I am no more fervent than before; but it seems to me that after a stormy voyage I have sailed into a peaceful harborage and that the happiness I feel on account of this, continues uninterrupted to this very day.”

After entering the Catholic Church, Newman suffered misunderstanding, hostility, calumny, and accusations of hypocrisy. All this he bore in silence, as did Christ before Pilate. He reacted only when the accusations called his fidelity and commitment to the Catholic Church into question. He never stopped loving those who turned against him after his conversion.

In February of 1846, Newman set out for Rome. There he entered the Collegium De Propaganda Fide to study theology in preparation for his reception of Holy Orders. After his ordination, Newman wrote of the Eucharist as follows: “Nothing so fills me with joy and solace, nothing so speaks to my heart as the Holy Mass. I could partake in it forever without end and never grow weary of it. It is the greatest action that could ever take place in the world. The Eternal One stands at the altar as the One who was in body and blood, before Whom angels bow, and demons tremble. Christ wrought the unceasing miracle of His Body and Blood under visible signs….And He gave His priests the power to enact what He enacted. He entrusted Himself to the hands of sinners. A feeble, ignorant and unenlightened, sinful man, by the power of the priestly authority imparted to him, brings the One On High to the earth, confines Him in a small tabernacle, and distributes Him to sinful people….It is clear, my brethren, that in confessing God to be the Almighty, we possess only partial knowledge of Him. If we wish to know Him fully, we must know Him in the Eucharist, as the One who bears the name ‘God is with us’ and ‘Jesus’ (God is Salvation).”

The Holy Father in Rome, Pius IX, authorized Newman to found oratories of St. Philip of Neri on English soil. He named Newman superior of the first such foundation in Birmingham. And there, from 1848 on, he served, writing articles and books, ministering to the Irish workers, and publishing The Rambler, a periodical for Catholic intellectuals. Newman’s views were well ahead of their time and laid the groundwork for the First and Second Vatican Councils. Before long Newman founded another oratory in London. At the request of the Pope and the Irish episcopate, he assembled a group of brilliant professors and founded the Catholic University of Dublin in 1854. There he served as rector until 1858.

Newman was convinced that anyone who sought the truth honestly would eventually end up joining the Catholic Church. He held that “in any real philosophy there is no middle ground between Atheism and Catholicism. A truly consistent mind must declare himself for the one or the other.” Protestantism stood between these two positions. Newman set forth a clear principle of distinction. “There are but two alternatives, the way to Rome and the way to Atheism: Anglicism is the half-way house on the one side, and Liberalism is the half-way house on the other.”

The years 1864-1874 were Newman’s most fruitful period in terms of his theological output. Many of his articles, books, and poems became famous throughout the world.

In 1879, in recognition of Newman’s contribution to the development of theological thought, Pope Leo XIII appointed him a Cardinal of the Catholic Church. For his cardinalate’s coat of arms Newman took the motto: Cor ad cor loquitur—“Heart speaketh to heart.”

In delivering his sermons, Newman had a preternatural gift for raising men’s hearts. He had a genius for eloquence and piety rarely encountered. His chief concern was to arouse in men’s hearts a living faith and an attitude of obedience to God. To seekers after the truth, he gave the following advice: “You must create in yourselves such a disposition as to be ready to commit yourselves entirely into the hands of God, and He will lead you to perfect obedience.”

He cautioned contrite sinners against impatience, urging them not to overburden themselves with prayer and penances. He advised them to begin with small mortifications and then allow themselves to be lead by their confessors. Blessed Cardinal Newman warned novice Christians that the way of faith would bring trials: “I shall be put to the test: my intellect will be put to the test, for I shall have to believe; my feelings will be put to the test, for I shall have to be obedient to God rather than follow my own inclinations; my body will be put to the test, for I shall have to keep it in check….Do not worry, go forward. ‘Heaven is not for cowards,’ St. Phillip used to say. Call on the Savior of men. He will hear you. He will heal all the wounds that you suffer while you serve Him.”

Blessed Cardinal Newman died on August 11, 1890. Before his death he requested that his gravestone bear the words: “Ex umbris et imaginibus in Veritatem” (From shadows and images to the Truth).

“Be on your guard that the world does not lead you astray!” So Blessed Cardinal Newman speaks to us today. “[The world] would convince you that only it is reasonable and wise, that religion is a relic of the past….It will call evil good and good evil. And so you will surely be tempted, but ‘Watch and pray that you may not undergo the test’ (Mt 26: 41). Either you will conquer the world, or the world will conquer you. Choose, and remember: ‘For freedom Christ set us free; so stand firm and do not submit again to the yoke of slavery!” (Ga 5: 1). Let us begin with faith. Let us begin with Christ. Let us begin with His cross and the humiliations to which He leads us. Let us allow ourselves to be drawn by the One, Who was raised up, so that He might thus give Himself and all things to us. Let us first seek the ‘kingdom of God and His righteousness,’ and all these things ‘will be given to you besides’ (Mt 6: 33). Only those who have come into contact with the invisible world can really enjoy the things of this world. Only those who have first learned to forgo and renounce it can enjoy the world. Those who have first fasted are able truly to feast. Only those who have learned not to abuse the world are able to enjoy it, and only those who accept it as a shadow of the future world and would leave this world for that future world shall inherit it.”

Prayers of Blessed Cardinal Newman

My great God, Thou knowest all that is in the universe, because Thou Thyself didst make it. It is the very work of Thy hands. Thou art Omniscient, because Thou art omni-creative. Thou knowest each part, however minute, as perfectly as Thou knowest the whole. Thou knowest mind as perfectly as Thou knowest matter. Thou knowest the thoughts and purposes of every soul as perfectly as if there were no other soul in the whole of Thy creation. Thou knowest me through and through; all my present, past, and future are before Thee as one whole. Thou seest all those delicate and evanescent motions of my thought which altogether escape myself. Thou canst trace every act, whether deed or thought, to its origin, and canst follow it into its whole growth, to its origin, and canst follow it into its whole growth and consequences. Thou knowest how it will be with me at the end; Thou hast before Thee that hour when I shall come to Thee to be judged. How awful is the prospect of finding myself in the presence of my Judge! Yet, O Lord, I would not that Thou shouldst not know me. It is my greatest stay to know that Thou readest my heart. O give me more of that open-hearted sincerity which I have desired. Keep me ever from being afraid of Thy eye, from the inward consciousness that I am not honestly trying to please Thee. Teach me to love Thee more, and then I shall be at peace, without any fear of Thee at all.

Holy art Thou in all Thy works, O Lord, and, if there is sin in the world it is not from Thee—it is from an enemy, it is from me and mine. To me, to man, be the shame, for we might will what is right, and we will what is evil. What a gulf is there between Thee and me, O my Creator—not only as to nature but as to will! Thy will is ever holy; how, O Lord, shall I ever dare approach Thee? What have I to do with Thee? Yet I must approach Thee; Thou wilt call me to Thee when I die, and judge me. Woe is me, for I am a man of unclean lips, and dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips! Thy Cross, O Lord, shows the distance that is between Thee and me, while it takes it away. It shows both my great sinfulness and Thy utter abhorrence of sin. Impart to me, my dear Lord, the doctrine of the Cross in its fullness, that it may not only teach me my alienation from Thee, but convey to me the virtue of Thy reconciliation.